A Look Back at the Okoboji Flooding: Devastation on the Lakeshore

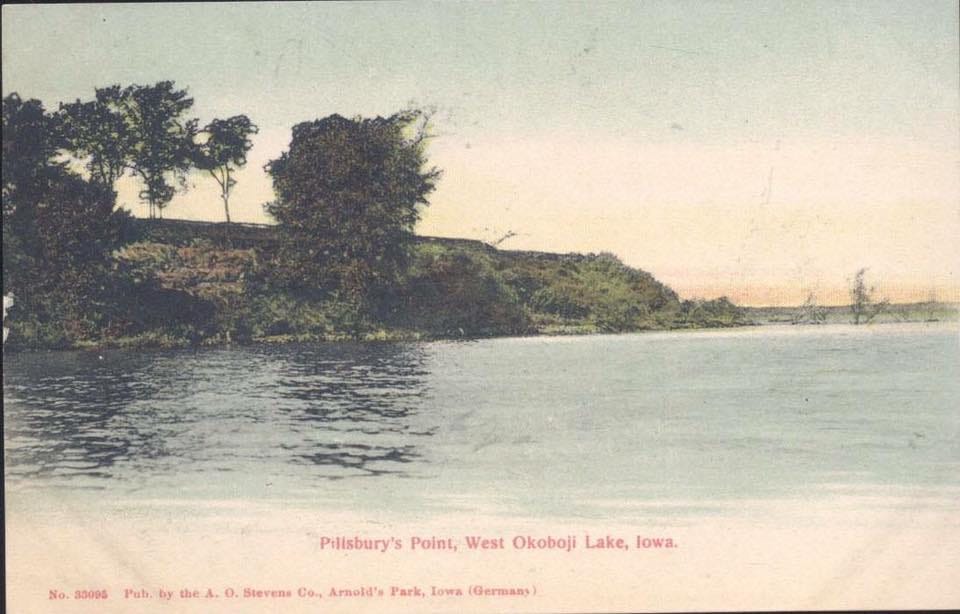

The Story of Pillsbury Point: From a Massacre to an Amusement Park

It has been six months since the most devastating weather event in recorded history in terms of high-bank collapse at Iowa’s premier resort region.

The full extent of the damage from the mid-June flooding at Okoboji remains under review. Michael Hawkins, district fisheries management biologist at Spirit Lake for the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, said in an interview that an engineering firm hired by the State to provide a detailed assessment of the damage is nearing completion of its work.

The work has included an inspection of 60 miles of lake shoreline in Dickinson County in an effort to inventory every high-bank collapse. The process also included something called drone photogrammetry, which is designed to provide a three-dimensional modeling of the massive bank collapses.

Altogether about 70 privately owned lake cottages experienced high-bank collapses. A significant majority of these were on West Lake Okoboji. Several, however, were on East Lake, mostly in two areas -- Francis Sites, near the north end of the lake on the west side, and Arthur Heights on the east side. There was one high-bank collapse on Spirit Lake, Hawkins said, and six to 12 on Silver Lake, a small, shallow natural lake near the city of Lake Park, Iowa, in the northwest corner of Dickinson County.

The high-bank collapses will be expensive to repair, and the responsibility will fall mostly to the individual property owners. Repair costs for individual high bank properties are expected to run in the mid-six figures.

There also was significant shoreline damage just below the usual non-flood high water mark at what is called the toe of the bank. The state is responsible for repairs at the toe of the bank up to about 2.5 feet above the usual non-flood high-water mark. But on high banks, that leaves the homeowner with the great majority of the repair cost.

One of the major areas of damage involving public property was the high-bank collapse at Pillsbury Point State Park, which is Iowa’s smallest state park at 6.5 acres but also one of the most historic areas in the entire state.

The story of Pillsbury Point: From a massacre to an amusement park

Pillsbury Point State Park is a narrow strip of lakeshore land just south of Pillsbury Point toward the south end of West Lake.

It was the site of the Spirit Lake Massacre in 1857.

Iowa was in its tenth year of statehood in 1856 with the Civil War, the deadliest in Ameriocan history, just around the corner. Meanwhile, a slowly progressing westward expansion of European-American settlement in the northern plains arrived at the Okoboji area, and marked the first white settlement in Dickinson County. The settlers – about 40 men, women, and children – arrived from various locations in Iowa and Minnesota and were attracted to the shoreline area near what later would become Arnold’s Park on West Lake Okoboji.

They barely had time to settle into their new cabins for the winter of 1857 when a renegade Sioux war chief, Inkpaduta, whose family had been murdered by a drunk, Caucasian whiskey trader, set out on a murderous chain of raids targeting white settlements in northern Iowa and southern Minnesota. The renegade band arrived at Spirit Lake on Saturday, March 7, 1857.

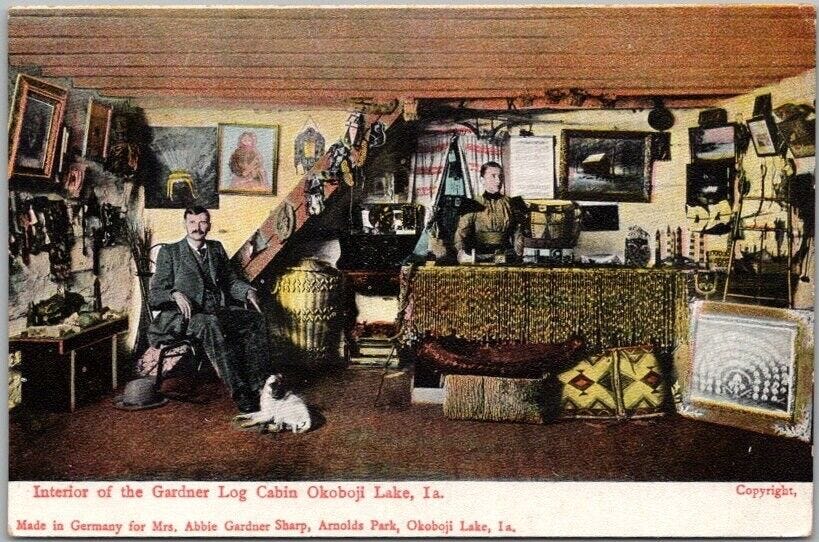

They murdered more than 30 European-Americans, all settlers or their guests residing in eight cabins at what later would become Pillsbury Point, named for the Rev. Samuel Pillsbury, who owned the property in the 1860s. They also kidnapped four of the women from these cabins. The murder victims included eight members of the Rowland Gardner family residing in a one-room log cabin the family had built. Abbie Gardner, then 13, was among the four women kidnapped. Two of the four women were murdered in captivity as Abbie was forced to watch. Abbie was the last of the two surviving women to be ransomed, after 84 days. She was freed by the Indians in return for two horses and supplies of gunpowder, tobacco, blankets, and yard goods. Abbie, still age 13, soon married Cassville Sharp, 18, a relative of another family murdered in the massacre.

They did not have a happy life. They moved around a lot, scraping to get by, and had three children. One, a daughter, died in infancy. A son was killed in a robbery at age 40. The remaining child, a son, died a few years later in the Lunatic Asylum at Cherokee, Iowa. Abbie and Cassville eventually separated; he remarried quickly. In 1891, she wrote a book about her kidnapping and life with the Indians, then used the profits from it to repurchase the family property at Pillsbury Point.

She converted the cabin and surrounding property into one of the Lakes Area’s earliest tourist attractions and persuaded the Iowa Legislature to build a monument to the massacre victims nearby. She died in 1921 at age 77 and is buried with her family across the road from the monument.

Pillsbury Point today

Today, more than a century later, the Gardner Cabin continues to exist as a significant Okoboji tourist attraction.

The high bank at Pillsbury Point, however, collapsed down to the lakeshore in last June’s flooding. The problem at Pillsbury Point, Hawkins said, was that the high bank areas were in the midst of a multi-year restoration project when the flooding hit. The toe area, especially, was targeted for repair. Native vegetation was being restored to better hold the soil in place, but the roots had only one year to develop. Another year of development and continued plantings could have made a difference, he said.

The restoration work at Pillsbury Point also was slowed by the fact that it is an “archeological hotbed,” Hawkins said, referencing the area’s historic role. Various agencies and organizations committed to historic preservation have to sign off before major ground repair work can begin. “It’s a challenging place to do construction work,” he said.

Hawkins expects that FEMA funding (Federal Emergency Management Agency) will be available to repair this damage because it is public property, but he added that if there is any shortfall, the state has committed to pick up the difference.

A rainfall like never before

The total rainfall leading up to the June flooding included 14.5 inches in one 48-hour period, with most of that rain falling within a 36-hour timeframe.

Although previous major floods at Okoboji, in 1993 and 2018, also resulted from extraordinarily heavy rainfall in relatively short periods of time, there were some major differences this year that made the lakeshore damage worse, Hawkins said.

For one thing, the ground already was saturated from ongoing heavy rainfall in the weeks prior to the flooding. Thus, when the 48-hour drenching occurred, the ground could not absorb any additional water. It all ran off into the lake from the top of the banks. The torrent of direct rain plus drainage runoff resulted in catastrophic failures of the high banks, some of which rise as high as a two-story house and also angle sharply down to the shoreline.

Additionally, there are some man-made situations that increase the runoff into the lake, thus adding to the total force of the running water. Paved areas, including streets and driveways, and slanted rooftops on lakeshore dwellings can send additional rainwater toward the lakeshore. Inevitably, the water flows toward a low spot on the shoreline, then cascades down the bank taking shallow plantings including shrubs and bushes with it. Stairways and small structures on a high bank also can get swept aside by the cascading water.

“It overwhelms the stormwater system,” Hawkins said. “It’s going to make its way to the lake. It’s going to overflow.”

Another factor is that the original prairie of the Iowa Great Lakes region consisted of bur oak trees and deep-seeded prairie grasses, both of which could better hold the soil in place during heavy runoff situations.

“Most of that prairie is gone. It’s been replaced by invasive plants and non-native plants and shrubs,” Hawkins said. In their place, he said, we have “shallow-rooted shrubs and trees that do not have good holding capability on that shoreline.”

In addition, the toe bank portion of the lakeshore has been washed out in some places. There is minimal rock and a lot of exposed bare dirt near the water line. “The waves are just able to continuously come in there and pull soil out,” Hawkins said. The best solution, he said, is “armoring that toe with . . . a bit of native fieldstone.”

What will the nutrients from the flood do to the lakes?

Yet another adverse situation stemming from the flooding was the enormous wash of nutrients into the Iowa Great Lakes. Phosphorous, a component of fertilizer routinely used with the Iowa Great Lakes watershed, produced enormous blue-green algae blooms throughout the lakes area in the weeks and months following the mid-June flood.

But Hawkins said he is hopeful that this could be no more than a one- or two-year problem. The long-term trend has been improved water quality in the lakes over the past 20 years, he said, with water clarity improving from 10 feet depth to 20 feet. “I hope there’s enough resilience there to literally weather that storm,” he added.

NOTE TO MY READERS: I write this column, Arnold Garson: Second Thoughts, as a member of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative. You can subscribe for free. However, if you enjoy my work, please consider showing your support by becoming a paid subscriber at the level that feels right for you. The cost can be less than $2 per column.

Iowa Writers Collaborative Roundup

Linking readers and professional writers who care about Iowa.