Presidential endorsements in American newspapers had a good run – more than 150 years – and America is the better for it.

Their disappearance, beginning 5-10 years ago and mushrooming this year, has been a product of changing times for newspapers and newspaper ownership, and the increasing divisiveness in our society. Though explainable, it is sad and unfortunate.

It is worth remembering that newspapers got into the endorsement business because the owners and editors knew that an informed electorate would be advantageous to the country as well as the newspaper industry.

Both would grow stronger.

Endorsements would sell newspapers, but they also would provide a unique, deep focus on the candidates and their campaigns.

Newspapers also were stepping in to fill a gap, however.

In the age of colonial America, newspapers were the only method of mass public communication that existed. Formal presidential endorsements did not yet exist, but politics was the mainstay of newspaper content, and there was little doubt among readers about which candidates the newspaper favored.

Things began to change in the 1830s.

Advancements in technology reduced the cost of manufacturing paper and producing the newspaper itself. New personalities, including Benjamin H. Day, Horace Greeley, and James Gordon Bennett, entered the business and began reimagining newspapers from top to bottom.

Why did the selling price of the newspaper have to put the product out of range for the working class? What could be done to make the content more interesting and timely? Was there a more efficient way to distribute newspapers to larger numbers of people?

The answers to these questions: It didn’t. A lot. Yes.

Editors added observation and interviews to the content-gathering techniques. They pursued human interest stories about ordinary people doing extraordinary things. They hired young boys to stand on street corners and sell newspapers to passersby.

Most important, the newspaper owners dropped the price of a newspaper to one penny. In today’s terms, that would have been the equivalent of a drop from as much as $1.50 a copy to less than 20 cents a copy.

Circulation volumes skyrocketed. American newspapers suddenly became the first truly mass media in the history of the world.

The one thing that stayed the same: Politics remained a major focus for newspapers everywhere.

Horace Greeley, who founded the New York Tribune in 1841, used his penny press newspaper to promote Whig Party philosophies, ideas, and candidates, playing a role in the election of Whig president Zachary Taylor in 1848. When the Whig Party died, Greeley’s newspaper became a voice for what evolved as the liberal faction of the Republican Party. He ran himself for president in 1872 but lost overwhelmingly to the incumbent, who also was the general who had won the Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant.

In Louisville, Kentucky, George D. Prentice, who had come to the state in 1830 to write the biography of Senator Henry Clay, became the editor of another Whig Party newspaper, the Louisville Journal, later The Courier-Journal. He used his paper to aggressively promote Clay’s political agenda as well as his unsuccessful presidential campaigns in 1832 and 1844. Whether the newspaper formally endorsed Clay or not, it made Clay’s candidacy the talk of the town. Everyone knew that Prentice and his newspaper were supporting Kentucky’s favorite son for President.

The newspapers of this era may not have been making official endorsements, but they definitely were playing an important role by providing focus and information through their outright support for their candidates of choice.

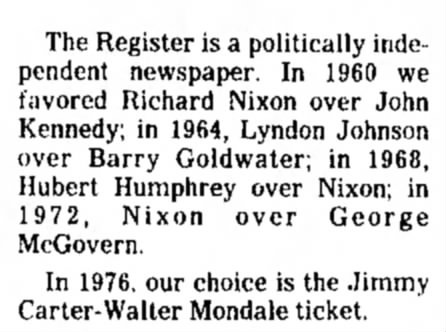

The New York Times, meanwhile, founded in 1851, made its first official presidential endorsement a year later for General Winfield Scott, the last Whig Party candidate for president. He lost to Franklin Pierce, a Democrat. The Times would endorse for president in every election after that, and many other newspapers began to do the same.

There is no definitive data regarding whether presidential endorsements make a difference in election outcomes. The best guess seems to be that in a close election during the heyday of endorsements, they might have mattered in some cases.

A study of the 1964 presidential election in the American Journal of Political Science in 1976 suggested that local newspaper endorsements could have been worth 5-6 percentage points for the endorsed candidates in 223 selected northern counties in the U.S. The study was limited but indicated that election results sometimes might have been affected by endorsements.

Another study, however, in Science Direct examining the period between 1960 and 1980 concluded, “we still know little about the role of newspaper endorsements in the history of U.S. presidential politics.” Most of the research done on 20th century elections “cannot estimate the persuasive effect of endorsements,” the article concluded.

In any event, by the 1980s, everything had begun to change again. Since that time, television, the internet, and the U.S. mail have become full-time and dominant providers of political information and disinformation. Newspapers, with greatly diminished circulation in most cases, meanwhile, are fighting to find a way to stay relevant.

The sad part is that presidential endorsements still would be meaningful, especially in exploring how the programs and ideas of a particular candidate might impact the issues that are important in a local or regional area. Agriculture and agribusiness are more important in the Midwest than elsewhere. Border issues are perceived differently in the Southwest than in the rest of the country. Railroad safety issues may be of greater concern in areas where there have been major derailments with chemical spills.

Unfortunately, however, there does not seem to be any road leading back to the era of the ubiquitous presidential endorsement.

It is a loss for the people of America.

NOTE TO MY READERS: I write this column, Arnold Garson: Second Thoughts, as a member of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative. You can subscribe for free. However, if you enjoy my work, please consider showing your support by becoming a paid subscriber at the level that feels right for you. The cost can be less $2 per column.

Iowa Writers Collaborative Roundup

Linking readers and professional writers who care about Iowa.

Thank you for reading and for the nice compliment.

Thanks for being a brilliant historian & teacher.