A remembrance of the sister and brother I never knew: The horrors of hydrocephalus

It has been more than 75 years since I was introduced to the phenomenon of hydrocephalus and 70 years next month since I was forced to revisit it. I was young, but the memories are vivid.

This column is a remembrance of the sister, Cathy Lynne Garson, and brother, Cary Garson, I never knew. Technically, they were half-siblings, but I did not think of them that way at that time.

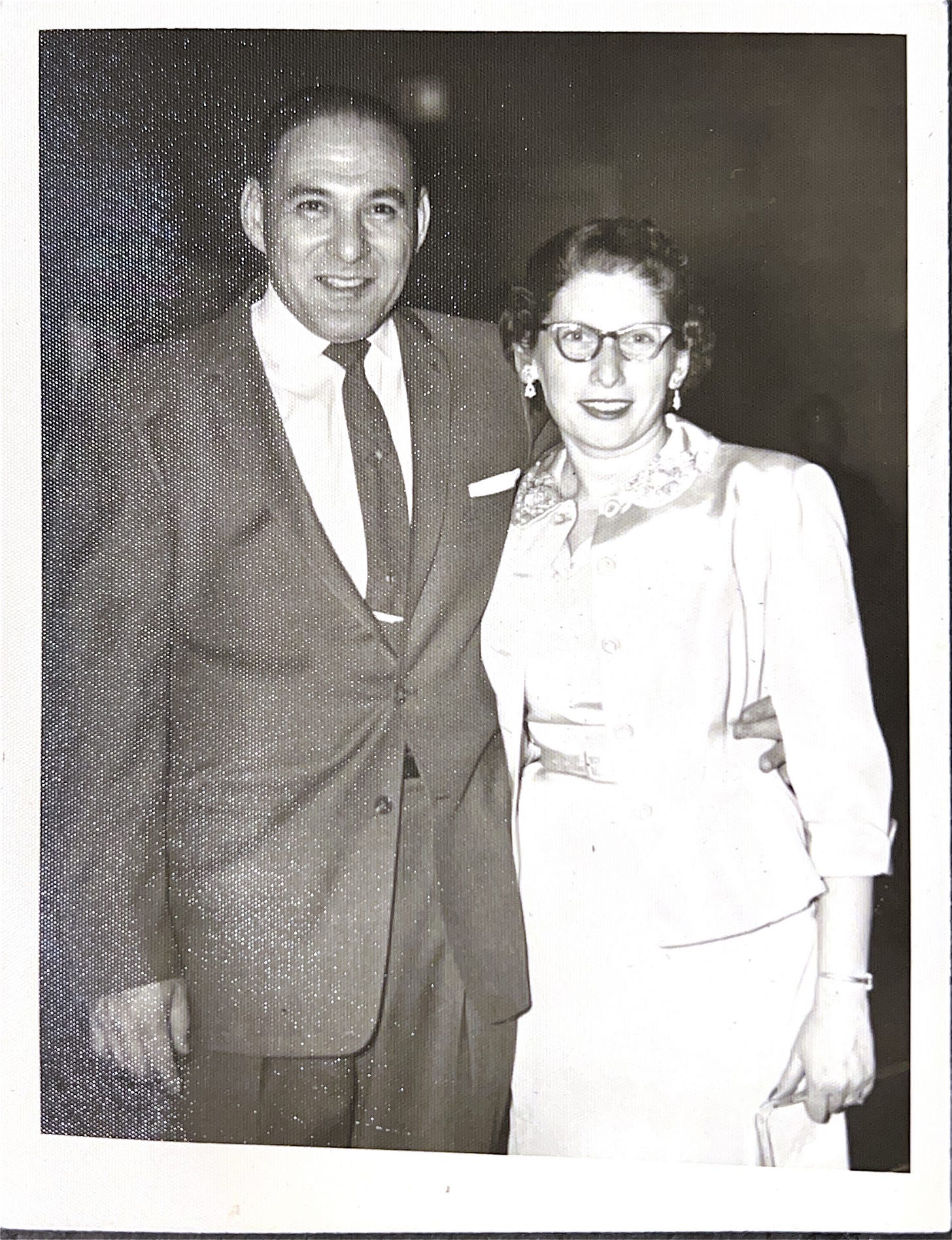

My parents, Dorothy and Sam Garson, knew almost nothing about congenital hydrocephalus in the late 1940s. Few people did know much about it.

But for those who did at that time, it would have ranked high on any list of the most devastating, unexpected tragedies that could strike during a couple’s early years of marriage.

Another technical fine point: Dorothy was my stepmother but was the only mother I ever knew. I loved her dearly. My birth mother had died of a cerebral aneurysm when I was 9 months old, and my father remarried quickly.

I was 6 years old in 1947 when I learned I was going to have a brother or sister. I was excited.

Dorothy’s pregnancy, her first, went well – until her physician observed something he didn’t like in the 9th month. Then, within 24 hours came an X-ray, an emergency cesarean section, and the news: Cathy Lynn Garson, born November 11, 1947, had a grotesquely enlarged head.

The first physician to document hydrocephalus: Hippocrates

Congenital hydrocephalus had been known for more than 2,500 years. Hippocrates documented it in the fifth century B.C. Many physicians, possibly beginning with Hippocrates, attempted to drain the excess fluid in the brain that caused the enlargement. But it was a complex medical problem at the time and nothing worked. The infants invariably died, usually within six to nine months.

Hydrocephalus is inaccurately known as water on the brain. It is a build-up of cerebrospinal fluid in the ventricles, a hollow area, deep within the brain. The brain produces this fluid, about a pint each day, which circulates through the brain, protecting it from trauma and delivering nutrients to it. The body maintains a constant amount of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain by continuously absorbing some of the fluid into the blood vessels.

Congenital hydrocephalus occurs when an abnormal formation of the narrow passageway between two of the brain’s four ventricles blocks the flow of the fluid and prevents the absorption of the excess fluid. The result is a relentlessly growing build-up of the fluid, which continuously enlarges the brain cavity and thus, the head. The pressure from the fluid impairs brain function as well as multiple body functions and results in death.

Estimates of the frequency of hydrocephalus are roughly in the range of one to two cases in 1,000 births.

Dorothy wanted to bring Cathy home from the hospital despite the dire outlook. Doctors counseled against it, and Sam persuaded Dorothy to go along with the medical recommendation. He went to court to have Cathy committed to the Beatrice State Home in Beatrice, Nebraska, about 40 miles south of Lincoln. Sam drove there in his 1938 Plymouth sedan with Dorothy holding Cathy in the front seat. They drove home alone.

Cathy lived in the Beatrice State Home her entire life – if her life can be described as living – until she died at age 9 months on August 29, 1948. Sam and Dorothy had gone to visit her, maybe two or three times – extremely painful trips.

Cathy’s birth, life, and death were horrible. Dorothy was severely depressed – and this was before the era of antidepressant medication. She cried much of the time and stayed in her bedroom most of the day. Somehow, over a period of several months, she managed to gradually piece her life back together and move on, finding solace in her family, her friends, her faith, and her volunteer work.

Looking back at it, her courage was amazing. Tragically, she would have to do it again.

Dorothy was pregnant for the second time in late 1953. Her physician had told her that there was no chance she would have another hydrocephalic baby. But he was watching closely for signs of any abnormality. For the first seven months, X-rays indicated normal development. Then, in her eighth month, an X-ray revealed a seriously enlarged head. Cary Garson, Dorothy’s second hydrocephalic baby, was delivered by cesarean section a day or two later on July 29, 1954. He had no middle name. Dorothy was not up to selecting one.

Although the doctor definitely was wrong about there being no chance of subsequent congenital hydrocephalus, it turns out that he had a 99 percent chance of being right. A study of subsequent congenital hydrocephalus published in 1984 showed a mere 1.1 percent recurrence rate.

A neurosurgeon in Lincoln had made a few attempts to drain the fluid in Cathy’s brain but succeeded only in extending her short, lifeless life by a few months. There would be no such attempts with Cary. Sam went to court again, and Cary followed his sister into a bedridden residency in a crib at the Beatrice State Home. He died there six months later, on January 31, 1955, and was buried alongside his sister, Cathy, in Mt. Carmel Jewish Cemetery in Lincoln.

At last: The first cure, about a year too late for our family

Ironically, it was another case of infant hydrocephalus in that same year that led to the first successful treatment of the condition. Casey Holter was born November 7, 1955, and developed meningitis shortly after birth, which subsequently blocked the flow of cerebrospinal fluid from the brain to the spine and caused hydrocephalus. Although Casey’s hydrocephalus was acquired rather than congenital, both forms of the condition lacked effective treatment options at the time and resulted in certain death.

Casey was being treated at a hospital in Philadelphia, where experiments involving the implant of a device to drain the excess cerebrospinal fluid in hydrocephalic infants had begun in 1949. However, there were issues with the design of the implant device and the materials used in making it. As a result, it had not yet worked. However, as Casey’s father, John Holter, a hydraulics technician, watched his son failing, he was struck with a new idea for the device.

Within a few weeks, he invented a medical valve that addressed all the issues. It allowed continuous drainage of the excess fluid while still retaining enough of it in the brain cavity to do the work it needed to do. It was air-tight when the fluid wasn’t draining, thus preventing any backwash of other bodily fluids into the brain. Holter then solved the last major problem by finding a new material with which to construct the valve – a material that could be sterilized and that the body would not reject: Silicone, then a newly developed product.

The pioneering surgery using Holter’s new valve worked in relieving Casey’s hydrocephalus. The fluid drained and his head returned to normal size. But Casey had developed multiple serious health issues from meningitis and died of a brain seizure at age 5.

Improvements in Holter’s valve were made in 1960 by another father of a hydrocephalic child, the author Roald Dahl, who partnered with a neurosurgeon and a toymaker specializing in small hydraulic pumps.

The breakthroughs provided a foundation that would transform the treatment of congenital hydrocephalic lives. Today, there are many styles and models of valves for hydrocephalus. The surgery for hydrocephalus works like this: A catheter is inserted from the back of the head deep into a ventricle of the brain. The valve is installed in the catheter line at the back of the head, thus controlling the amount of fluid that is drained while preventing backwash. The catheter winds down through the neck and chest into the abdomen, where the fluid is harmlessly drained off.

A 2012 study by the National Institute of Health showed a long-term survival rate of 83 percent – versus a zero percent survival rate prior to the development of the surgery.

Whatever the intense level of anguish Dorothy and Sam experienced with the birth and death of Cathy, it would be multiplied something like ten-fold by the birth and death of Cary. Among other things, they now had to face the reality that Dorothy never would have children of her own. One evening shortly after Cary was born, while Dorothy was still in the hospital, Sam went to the home of his eldest sister, Johanna (Joie) Davidson, where I had been staying while Dorothy was in the hospital. He embraced Joie, put his head on her shoulder, and sobbed – and sobbed.

Dorothy essentially went through the same cycle of serious depression as she had seven years earlier. But this time, it took her several months longer to recover.

Years later: A stunning family discovery

Dorothy always believed that the fact that her parents were first cousins might have had something to do with the apparent genetic flaw that caused her to produce two babies with congenital hydrocephalus. But a stunning discovery I uncovered through my genealogy research in 2016 suggests that there might have been a genetic flaw that ran more broadly in her family.

Dorothy had a first cousin in Los Angeles who fathered a hydrocephalic baby born in 1954. The baby died at age 9 months. In an incredible coincidence, the baby was born one day after Cary Garson. The difference was that the cousin and his wife in Los Angeles proceeded to have two more daughters, neither of them hydrocephalic. Dorothy never knew anything about this situation.

But now there were two sisters with hydrocephalic grandchildren: Dorothy’s mother, and the mother of Dorothy’s cousin in Los Angeles who fathered a hydrocephalic infant. Could the hydrocephalic gene trace back to the mother or father of these two sisters?

For Dorothy, the tragic loss of her babies never was far from the top of her mind for the rest of her life. One day about 55 years after Cary’s death, Dorothy was in a skilled nursing home in Columbus, Ohio during her final illness – a matter of about six weeks. She was a few weeks from her 90th birthday.

She was watching something on television and the subject of what it is like for a mother to care for and bond with a newborn happened to come onto the screen. I was in the room with her.

“That’s something I wasn’t meant to experience,” she whispered.

It was also the thing she wanted most.

Adapted from Dorothy’s Story by Arnold Garson, 2016.

Thank you for the well-written and scientifically accurate translation into laymen's language of both the nature and treatment of hydrocephalus, as well as sharing the familial and individual consequences.

What tragedies both of your parents endured. Your genealogical research shed light on the mystery so many decades later. An absorbing, and heartbreaking, column.