How the Okoboji area almost became a part of a state not named Iowa

It would have changed everything

This story is about the Iowa Great Lakes and how they almost did not come to be. Or, at least how they almost came to be located in a state not named Iowa.

The result likely would not have been good either for Iowa or for what we generally describe as the Lakes Area.

It is a complex and forgotten twist of history that is intricately linked to something many would like to forget – the reality of slavery in nineteenth-century America.

Oddly, even though slavery never was legal in Iowa, even when it was a territory, the story of Iowa statehood – and the story of how the Iowa Great Lakes might have ended up in Minnesota, Nebraska, or even South Dakota – is a story about the politics of slavery.

For seven decades preceding the Civil War, the admission of states to the Union was linked to the North-South split over slavery. It was an issue, particularly in the U. S. Senate where every state, regardless of size, has two votes, and the balance of power between slave and free states often was tied or no more than two votes one way or the other. For Iowa, the slavery issue influenced both the timing of its statehood and the drawing of its borders.

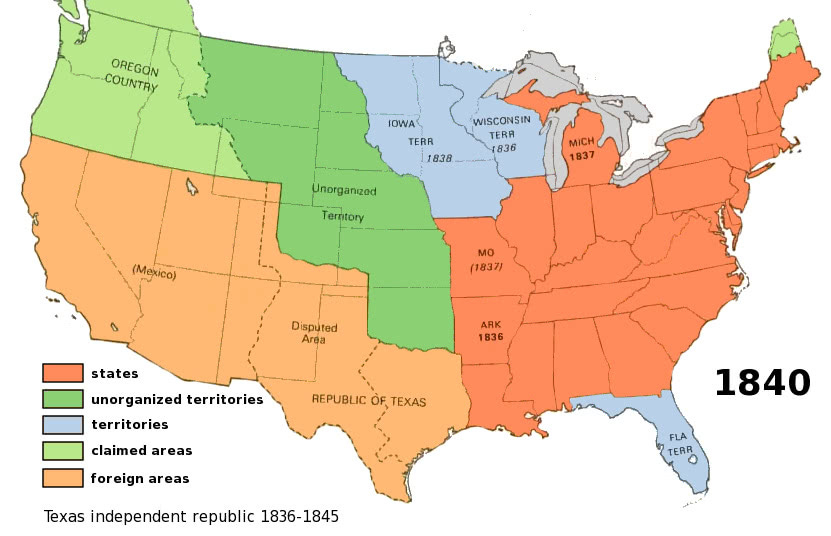

The Iowa Territory was formed in 1838. During its early years as a territory, most Iowa residents were focused on the job of setting up the territorial structure. They are not thinking about statehood. As the population grew, however, it was inevitable that Iowa’s agenda would come to include statehood. Then, in 1845, something happened in a distant part of the country that put Iowa on the statehood fast track. On March 3, 1845, Florida, the last territory in the eastern third of the country and the last slave territory in the country became the twenty-seventh state.

Prior to Florida’s statehood, the states had been evenly split – 13 slave states and 13 free states. Slavery, however, was such an intensely hot issue that Congress was not able to enact Florida statehood without finding a way to maintain the 50-50 split. An agreement was reached to pair Iowa, which seemed to be the free territory most ready for statehood, as a free state with Florida as a slave state. Translation: Iowa would be the next state to be admitted after Florida, and it would happen soon. The urgency of Iowa’s admission increased greatly at the end of 1845 with the somewhat abrupt annexation of the Republic of Texas, which had seceded from Mexico several years earlier. Texas became the fifteenth slave state – versus 13 free states.

The free states desperately wanted to move forward with Iowa statehood, per their deal regarding Florida statehood. They still would be one state away from a 50-50 split, but the remaining territories in line for future statehood were heavily anti-slavery tilted.

First, however, Congress and the residents of Iowa had to agree on the boundaries for the new state of Iowa. It was not an easy agreement to reach.

The free states wanted to keep the State of Iowa relatively small. This would leave room for several additional free states to be created from the remaining free territory of Iowa, which stretched from Missouri to Canada and west into what later would become the Dakotas.

At first, the only thing that was certain about the boundaries for the State of Iowa was that the east boundary would be Mississippi River, thus making the state contiguous to the existing state of Illinois. The north, south, and west boundaries all were up for debate.

For the Spirit Lake-Okoboji area, this debate and the ultimate settlement of Iowa’s boundaries would have profound consequences.

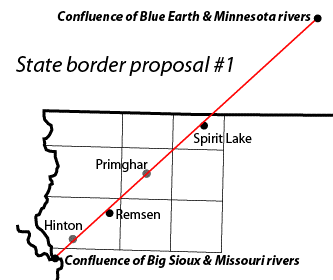

The first Iowa statehood border proposal to go to Congress in 1846 excluded most of the three major bodies of water – all of Spirit Lake, the north half of West Lake Okoboji, and the northern tip of East Lake Okoboji. The majority of the surface area of the three big lakes probably would have remained in what was left of the Iowa Territory, likely ending up in Minnesota at a later time.

The proposal for the western portion of the north border of Iowa was a 45-degree diagonal line running northeast-southwest approximately through what is now the Wal-Mart intersection of Highways 9 and 71 in Spirit Lake. This proposed diagonal state line extended southwest, cutting through West Lake, to about Sioux City. It also extended northeast to Blue Earth, Minnesota, about 135 miles in all. All of Lyon, Osceola, and Sioux Counties, and parts of Dickinson, O’Brien, and Plymouth Counties would have been on the other side of the Iowa state line. Congress rejected the plan. The reasons are unknown, but one factor likely was that diagonal line.

There would be few states created with straight-line diagonal borders. Horizontal and vertical lines, and generally north-south or east-west rivers, would be the norm for the great majority of state boundary lines. That was primarily because farmers, who held substantial political power, did not like diagonal lines of any kind – not for state or county boundaries and, later, not for paved highways. Farmers plowed their fields along horizontal and vertical lines. They did not want their established travel paths disrupted with the creation of diagonal lines.

Congress then offered its boundary proposal for Iowa, cleaving off the entire western third of what ultimately would become Iowa and extending the north boundary of the state northward to a line running east-west in Minnesota from Blue Earth through Owatonna and Rochester. The result would have been a state roughly resembling the shape of Indiana. The Iowa Great Lakes would have remained in territorial status, destined to be situated within one or more of the future states of Minnesota, Nebraska, and South Dakota.

This proposal was rejected by the residents of the Iowa Territory. They wanted a state running river-to-river from the Mississippi on the east to the Missouri River on the west. They saw an advantage in having two navigable rivers serving as transportation corridors for what even then was understood to be the new state’s major asset: its fertile farmland and the crops that land would produce.

Yet another boundary proposal then emerged, at least the third, and it gained acceptance both in Congress and among Iowans. The statehood bill, providing for Iowa’s present boundaries, was signed into law by President James K. Polk on December 28, 1846. It was a pivotal moment. Iowa would be the first of six consecutive free states to be admitted over the next 14 years. This would forever tip the political balance regarding slavery; also, in effect, sealing the eventual secession of the South and assuring civil war.

It is hard to imagine Iowa without its three distinctive lakes in Dickinson County; likewise, it is hard to imagine these lakes being located partly or entirely within a state other than Iowa.

Within Iowa, this Lakes region is unique. But if some or all of this area had fallen within Minnesota, it likely would have blended into the mix of that state’s 11,000 other lakes, many of which resemble the Iowa Great Lakes. The transportation lines – railroads and highways serving the Lakes area – likely would not have been designed to provide easy connections for residents of Des Moines, Cedar Rapids, and Iowa’s other large cities as well as its across-the-river big-city neighbor, Omaha.

A significant factor in luring Iowans to the Okoboji area in the summers was the aggressive statewide coverage of The Des Moines Register. Its coverage was extensive, including who was going there, who was coming home, who was attending various parties, and what conventions and meetings were being held there. Its classified advertising columns were a marketplace for Okoboji businesses and real estate. The Register had its own airplane and would fly to Okoboji to cover major news events. Would Iowans have come to the lake in such large numbers without The Register’s coverage? Moreover, The Register’s statewide footprint was unusual, if not unique. It seems unlikely that a newspaper from any of the other three states would have filled the gap.

Ultimately, the summer cottage population that grew so rapidly in the Lakes area in the late 1800s was fueled primarily by residents of Iowa. Playing into this equation has to be the fact Iowa was a relatively large state in population. Yes, really. With almost 3 million residents, only nine of the nation’s 45 states in 1890 were larger than Iowa. Would that growth have come from any of those other three states? The case probably can be argued, but it seems doubtful. There was a lake every three miles in Minnesota. Nebraska and South Dakota were much smaller in population than Iowa. Plus, South Dakota was preoccupied – for good reason – with the development of the Black Hills as its resort area.

We will never know for sure how things would have played out if the Lakes had not been situated entirely in Iowa. But it seems hard to construct a scenario that resembles anything like what the area has become if that had been the case.

As for the final result: Maybe it turned on the Congressional aversion to diagonal lines, Maybe the slavery issue played into it in some way.

But it was absolutely the right result for most who have made the Lakes Area their summer resort destination.

Who knew! Fascinating common, Arnie. I’m now sitting here thinking how different politics in Iowa today would be if the state did not include that northwestern triangle!

Thank you! Learning something new about Iowa is a great way to start the day!