How the Spirit Lake Massacre led to an iconic amusement park at Okoboji

This is the story of how one of the most horrifying tragedies in Iowa's history gave way to the creation of one of the grandest tourist attractions the state has known, now in its 135th year.

The story begins in 1856. Iowa was in its tenth year of statehood. The westward expansion of white settlement in the United States was inching its way across the Upper Midwest. In the Iowa Great Lakes area, the first European-American settlers – about 40 men, women, and children – arrived that year from various locations in Iowa and Minnesota to become the first white settlers in and near what soon would become Dickinson County, Iowa.

Many of these settlers chose home sites near where the East and West Lakes come together, including an area that later would be known as Arnold’s Park.

They barely had settled into their newly erected cabins for the winter of 1857 when a raiding band of Santee Sioux Indians arrived. The band had been hunting in Woodbury County, Iowa, near Sioux City, the previous winter when one of the hunters was bitten by a white settler’s dog. The Indian shot the dog and the enraged owner savagely beat the Indian.

The Indians, led by a war chief, Inkpaduta, then set out on a murderous chain of raids targeting white settlers in Northwest Iowa and southern Minnesota.

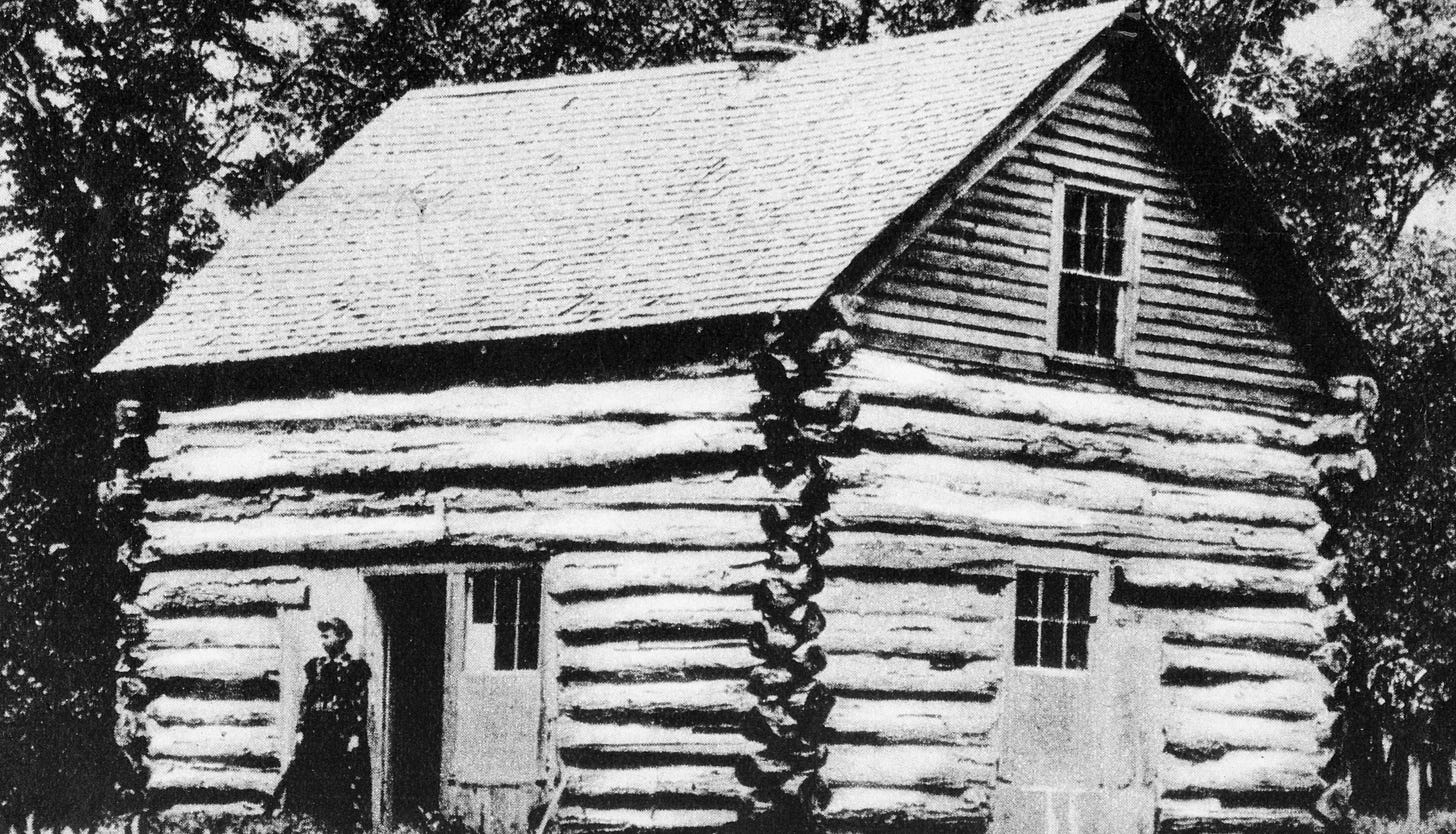

The band arrived at Spirit Lake, Iowa, on March 7, 1857. In five days, they murdered 30 European-American settlers and guests residing in eight cabins in the Okoboji area, and another five settlers in a settlement near what later would become Jackson, Minnesota. The victims included eight members of the Rowland Gardner family residing in a cabin on a sizeable plot of land at the southern shore of West Okoboji, close to what is known today as Pillsbury Point.

The Gardner family property eventually was acquired by J. S. Prescott, a Methodist preacher, who erected a few primitive buildings and made other improvements. In 1864, he persuaded an acquaintance, Wesley B. Arnold, to relocate to the Lakes area from Wisconsin. Arnold purchased Prescott’s property – the original Gardner family property – and quickly established his one-room cabin and the surrounding land as a rest stop and campground for travelers.

A primary travel mode of the era was horse and wagon, which required an overnight stop every 30-40 miles and trips often were planned to take advantage of stopover locations like Arnold offered.

Soon he began investing in improvements and acquiring additional land to enhance the standing of his property as an attraction for travelers. He began adding cottages and buildings in 1873. At first, there was no grand plan — just more buildings and campgrounds randomly added. He described the effort as building, “I know not what.” His work became more earnest and specific in 1882 after the first railroad to the lakes area was completed. He built the Arnold’s Park Hotel on the lakeside. He built a dance hall nearby. He soon added games and competitions – pool, billiards, tenpins (an early form of bowling), and an annual shooting tournament.

His property was, in effect, Party Central for the Lakes area.

And then, his daughter, Hattie, and a friend were conversing one evening and came up with the Big Idea – possibly, the idea of their lifetimes. They presented it to Hattie’s father: His property should become known as “Arnold’s Park.”

Arnold’s property began transitioning from a traveler’s rest and partying stop to an amusement park in 1889 with the construction of a 60-foot toboggan-style water slide. Visitors waited in long lines to experience the thrill of the slide into the lake.

In 1891, the Gardner family cabin was repurchased by one of the massacre survivors, Abby Gardner Sharp, who had been kidnapped and held prisoner by the Indians for 84 days at age 13. It has been a tourist attraction and monument to the massacre victims since that time.

Arnold died in 1905 leaving the park to his three daughters, two of whom, with their husbands, continued the development of what was becoming a full-blown amusement park. Arnold’s son-in-law, A. L. Peck, became the managing partner. A carousel was added in 1915, the Roof Garden in 1923, and the Fun House in 1929.

Personal aside: Ray McMartin, my wife’s first cousin, who spent his childhood summers at a family cottage on West Lake, recalls the wonder of the carousel in Arnold’s Park in the 1930s. It had an unusual feature – a lion with silver rings in its mouth. Riders would grab one of the rings as they went by. After several revolutions, the operator would slip in a gold ring. The next rider would grab it causing the lion to R-O-A-R.

In 1918, C. P. Benit, a farmer about 100 miles southwest of Okoboji who had been acquiring land in the Okoboji area, purchased a souvenir stand and soda fountain on the lakeshore near Arnold’s Park. Within a year, Benit had built the Majestic Roller Rink and a transition had begun. Benit Park, adjacent to Arnold’s Park, but independently owned and operated, had arrived at Okoboji.

The history of amusement parks in America

The arrival of amusement parks in America followed closely the arrival of electricity. Trolley carriers in bigger cities paid a flat rate for electrical service. Predictably, they began to search for ways to maximize revenue by getting more people to utilize their trolley lines during off-peak hours – evenings and weekends. The solution was to build small amusement rides near parks and resort areas along the trolley lines, creating family activity destinations.

Amusement rides became a growing sensation. Rides got bigger and the thrills got bolder. The first carousel was built at Coney Island in New York in 1876. The first roller coaster arrived in 1884, also at Coney Island; its top speed was about 5 miles an hour.

In the 1880s and ‘90s large-scale amusement parks began to appear in many larger cities, especially near lakes and the seashore.

Often, competing amusement parks would be situated within walking distance of each other. At Coney Island, three amusement parks operated in the 1890s – Sea Lion Park, Steeplechase Park, and Luna Park – and could attract, collectively, 1 million visitors in a single day in the summer.

By the 1920s, there were hundreds of amusement parks in America. It was the heyday of amusement parks, fueled by a perfect storm of situations and conditions that promoted their use and growth. Automobile travel was becoming common. Air conditioning was not yet common. The economy was booming. Television did not yet exist. Talking motion pictures did not arrive until near the end of this decade.

The battle of roller coasters on the West Okoboji shoreline

At Okoboji, Benit Park and Arnold’s Park competed aggressively on the south shore of West Lake for more than a half-century until they merged in the mid-1970s with Arnold’s Park as the surviving entity.

Arnold’s Park built its first wood roller coaster in 1914. It was replaced with a new and safer model in 1923. Then, in 1930, both Benit Park and Arnold’s Park began construction of new, larger, faster roller coasters.

In Arnold’s Park, the new roller coaster would be known as The Thriller. It was a major attraction for about 20 years but was dismantled in about 1950 as amusement parks faced economic pressures in a changing industry.

In Benit Park, the new coaster would be named the Giant Dips Roller Coaster, later to be renamed three times, finally taking the name that would stick, The Legend.

The Spirit Lake Beacon reported on March 20, 1930, that Benit’s new coaster would provide a ride of about 2,000 feet in length (a little more than one-third of a mile) and reach 65 feet in height. A construction crew of 200 men would be needed to build it. It was designed by a renowned roller coaster builder, John A. Miller, and had a top speed of 50 miles an hour. Today, The Legend stands as one of the oldest wood roller coasters in America and one of the last surviving John A. Miller coasters. It also has become the definition of its name: a Legend.

The Legend’s darkest day occurred in 1971. A teenager was killed when he stood up as the coaster was approaching its peak, known as The Point of No Return. There were no seat restraints at this time, and when the car lurched forward on the downhill run, the youth was thrown out of the coaster car and fell to the ground. As a result of the accident, the Iowa Legislature enacted the state’s first safety regulations and inspection process for amusement park rides.

The survival of Arnold’s Park

The Depression and World War II brought hard times for amusement parks in the U.S. Then, the arrival of the theme park in the mid-1950s transformed the industry, leaving many conventional amusement parks in the dust.

Arnold’s Park is among a scant few amusement parks of the 1920s that have survived and grown into the 2020s.

It has survived the Depression, a tornado (1968), a flood (1993), and an owner-developer who wanted to raze it and replace it with condos and a resort (1999).

The park has been owned and operated by a non-profit organization since 1999.

Good to hear from you, Pamela. Hope all is well.

Nice piece reminded me of this book we did https://icecubepress.com/2021/08/03/moon-of-the-snowblind/