One family's 115-year history on West Okoboji: A place for memories and togetherness

How two unrelated violent deaths shaped the Okoboji futures of two families

The unseasonably warm pre-spring weather has turned thoughts to Okoboji earlier than usual this year.

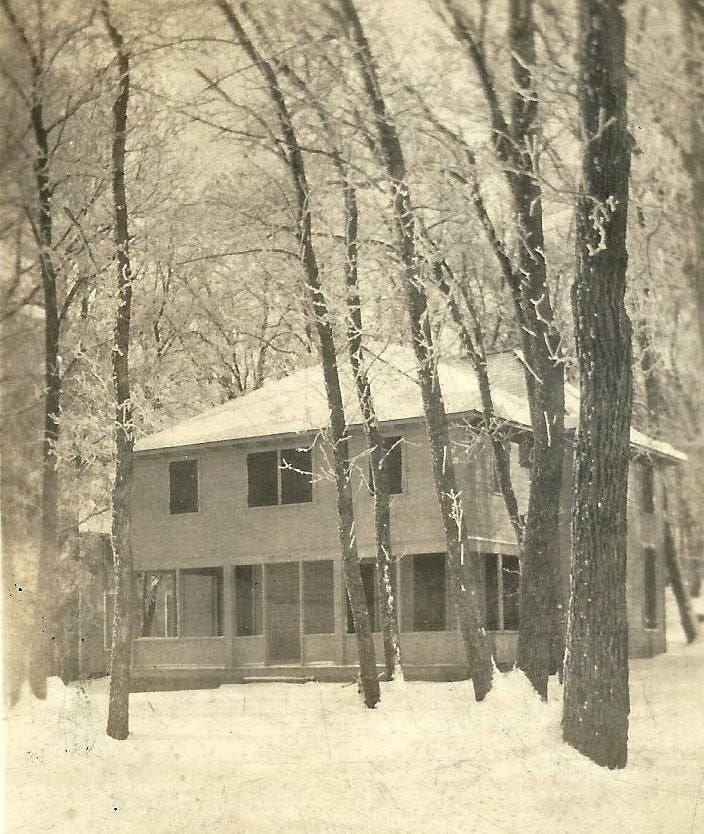

We soon will be saying “Hello” to the summer cottage on West Lake that my wife’s grandparents built 93 years. Clairdell Cottage – more about the name later – was built by Lynne’s paternal grandparents. Our grandchildren are the fifth generation to spend a part of every summer there. The cottage is filled with family and lakes memorabilia, still has many of its original furnishings, and its original footprint. Kitchen and bathrooms have been updated, but the goal has been to keep as much of the original cottage in place as possible.

The result is that it has been a major component of building memories, emphasizing the importance of building a sense of togetherness, and providing a footprint for keeping our family together into the future.

Lynne’s family history at Okoboji goes back farther than this cottage, however. It begins in the 1890s with Abraham Daughenbaugh, her great-grandfather.

Abraham was a Gowrie, Iowa, banker and real estate investor, who acquired a farm just north of Spirit Lake, Iowa, in 1899. He purchased the 160-acre property for $1,856, the Spirit Lake Beacon reported. Abraham was known to be a bargain-hunter in his real estate investments, but it is virtually certain that this one turned out to be a bargain that ran well beyond anything he could have expected. The price was $11.60 an acre, the equivalent of $430 an acre in today’s money. Except that farmland has appreciated at a significantly greater level than the cost of living. Dickinson County farmland today goes for $12,000 an acre and more. Too bad it is no longer in the family.

In any case, Abraham would visit the farm periodically to keep track of things and he became familiar with what the lakes area had to offer as a summer residential resort. He liked what he saw.

A few years earlier, in the early 1890s, William Gilley, a Carroll, Iowa, farmer, businessman, and civic leader, began spending summers at Okoboji. It was a two-day trip by horse and wagon – worth it, he felt because of West Okoboji’s breezes and location, more than 100 miles north of Carroll. This provided relief from the summer heat at a time before air-conditioning existed; a rule of thumb being that temperatures are about 10 degrees cooler for every 100 miles traveled, south to north.

In 1894, Gilley purchased a stretch of lakeshore property at the south end of West Okoboji a bit north of the bridge. He laid out the land in residential lots, about 50 feet of lakeshore each. It was just around the corner from the amusement park and what would become known as Pillsbury Point. Gilley built a cottage there for his family and then set out to sell the rest of the lots to his friends and business associates in Carroll.

Meanwhile, William L. Culbertson, a Pennsylvania native and Civil War veteran, had come to Carroll County in 1869 at age 25. He farmed for a couple of years and began a career in local politics as county auditor, then county treasurer. He moved to the city of Carroll and married a local girl, Ruth Olivia Johnson. In 1876, he purchased a small bank and was joined in operating it by two other investors. In 1895, the three men purchased the larger First National Bank of Carroll, merged it with their smaller bank, and soon had the largest bank in town. A year later, William Gilley sold lots on Gilley’s Beach on West Lake Okoboji to Culbertson and each of his two partners.

The Culbertson property at Okoboji was toward the north end of Gilley’s Beach, a 50-foot lot, but with 65 feet of lakeshore because the lake cuts a diagonal line across the front of the lot. The Spirit Lake Beacon described the new Culbertson cottage on June 25, 1897, as “a fine cottage at Gilley’s Beach. It is of good size, well planned, and well-constructed.”

Culbertson would continue his career in public service in Carroll on the County Board of Supervisors, in the State Legislature, on the City Council for 20 years, and on the School Board. He lived in one of the finest homes in town and was regarded as one of the wealthiest men in Carroll. He was active in the Republican Party and political insiders discussed him as an attractive candidate for governor in 1900, though he did not run.

Then, at 6:40 a.m. on Monday, October 19, 1908, he awoke at his home in Carroll, told his wife that he was not feeling well, and walked into the bathroom. He picked up a pistol he had hidden there the night before. He looked in the mirror and put the barrel to his right temple.

His wife found his body on the floor minutes later. He was 64.

It was a Page 1 news story in newspapers across Iowa. The word embezzlement was not used. But phrases like financial worry, land speculation, and using the bank’s funds, left no doubt about what had happened. Bank examiners moved in the same day. They closed the bank and it never re-opened. After a two-year investigation, the bank had paid out 30 cents on the dollar to its depositors – who had trusted the bank with $400,000 of their money, the equivalent of almost $14 million today.

Culbertson’s widow, Ruth, relocated with her unmarried adult daughter, Mary, who had worked at the bank with her father, to a small town of just 250 people in north central Wyoming, essentially, the middle of nowhere, presumably to get away from their familial embarrassment in Carroll. There was not a city of more than about 10,000 within 400 miles.

Abraham Daughenbaugh would have read about all of this in Iowa newspapers. He also would have known Culbertson through banking circles – the banks they owned were less than 60 miles apart – and the Republican Party, in which they both were active.

Eight months after Culbertson’s suicide, on June 24, 1909, Ruth Culbertson signed over the Okoboji cottage she had inherited from her husband to my wife’s great-grandfather, Abraham Daughenbaugh of Des Moines.

The price was $1,600, undeniably a bargain. The purchase included the cottage, which was about 12 years old, its furnishings, one rowboat, an undivided half-interest in a boathouse, and a stable with room for a carriage and two horses. There were many similar lakeshore cottages offered for sale in The Des Moines Register around this time, almost always in the $4,000 to $5,000 range.

Abraham Daughenbaugh died a year later at age 66. One day before he died, he met with a notary public at his home on Grand Avenue in Des Moines and transferred ownership of the Okoboji cottage to his wife for “$1 and love and affection.” Clearly, he wanted his wife, five children, and three grandchildren – one more would arrive a few years later – to have time to build the memories and create a sense of togetherness that a summer lake cottage can provide.

Over time, the cottage on Gilley’s Beach would be renovated and updated. Abraham’s descendants continued to own it and use it until it was sold in 2014.

In the summer of 1931, the youngest Daughenbaugh grandchild, Grace Staves, also from Des Moines, was spending the summer at this cottage with her mother. Across the lake and toward the north end, Clair and Adel Baird of Omaha, had moved into their new, recently completed summer cottage on Fairoaks Beach. Their son, William Baird, in college at the time, and his sisters spent much of their summers at the cottage.

Side story about cottage names: Until sometime after World War II, cottage names were common at Okoboji. The name Clairdell was a conflation of Clair’s and Adel’s given names. Similarly, the Daughenbaugh cottage on Gilley’s Beach eventually was named Graetta, a conflation of the given names of the two daughters — Grace and Henrietta — whose parents were the second-generation owners of the cottage. At Clairdell, the sign that once hung on the front of the cottage was removed and thrown into storage, probably in the 1950s. A portion of it was found in the 1990s, rebuilt and restored, and hangs today in the porch area of the cottage.

On Saturday nights, young people of the Lakes area routinely gathered at one of the several dance halls. There were five or six of them, including the Central Pavilion in a building now known as the Central Emporium in Arnold’s Park. At one of these Saturday night dances at this location in the summer of 1931, William Baird met Grace Staves. They were attracted to each other immediately and were married in 1935.

Ultimately, the cottage on Gilley’s Beach would be taken over by Grace’s sister, Jane Staves Clements. The cottage on Fairoaks Beach would become William and Grace Baird’s summer home in 1949. Lynne, her brother, and her sister would move from Gilley’s Beach to Fairoaks Beach with their parents that summer. Lynne is now the senior descendant of Abraham Daughenbaugh in the line that connects with Clairdell cottage.

My own summers at Okoboji were much different – two-week vacations each summer with extended family at Gerk’s Resort at the far north end of West Lake. But this story also, oddly, begins with a violent death.

My father, a widower, remarried in the summer of 1943, when I was 2. It was a time of war and gasoline shortages. My parents, from Lincoln, would have to select a honeymoon location where they could travel by bus or train. Okoboji seemed like a good choice. They stayed at Fillenwarth’s Resort.

They had such a good time that they persuaded other family members, my aunts, uncles, and cousins, to join them at Okoboji every year after that for their summer vacations for more than 25 years. The vacations were a family event and the family was in search of a resort that felt right for them and their needs. They tried three different resorts each of the first three years. None was what they wanted.

Then, in 1946, they discovered Gerk’s Resort at the north end of West Lake, a collection of maybe two dozen individual lakeshore cottages that constituted a summer vacation resort with amenities ranging from boats and docks to horseback riding. Once a week, Gerk made popcorn and held a big yard party for all the guests. Our extended family loved the location and amenities. There also was an attractive side benefit: They established a close relationship with Gerk and his family.

Gerk Jansen had been a barber in Sac City, Iowa, until the mid-1940s, when he heard about an Okoboji resort that was for sale at a bargain price. Rob Raebel and his wife, who had owned Raebel’s Resort, were attacked and robbed in their home at the resort in December 1944. The robbery netted no more than $40 to $60.

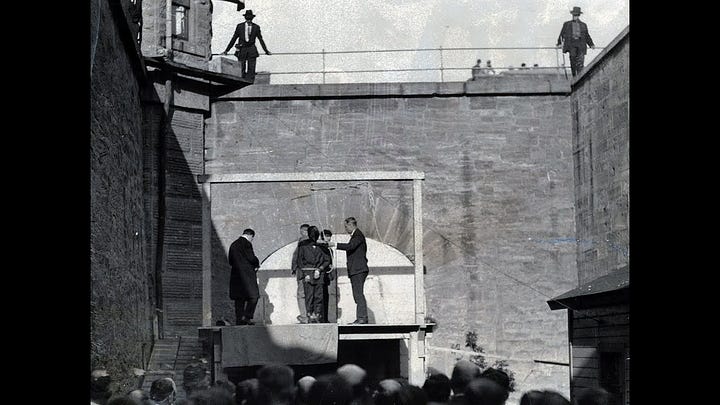

The two attackers were a father and son pair, who had worked for the Raebels the previous summer. They murdered Rob and severely beat his wife — attempted murder would be a more accurate description. The case has been compared to Truman Capote’s classic non-fiction book, In Cold Blood.

Mrs. Raebel survived and identified the attackers, who eventually were convicted and hanged simultaneously at the Iowa State Penitentiary in Fort Madison – the only father and son ever to receive capital punishment together in Iowa history.

The Raebel property went on the market, but the gruesome history seriously depressed its price. Gerk and his wife, Vera, decided to become resort operators. My family spent two weeks there every summer from 1946 through at least 1966.

My last visit to Gerk’s with my parents was in the summer of 1960. The following year, I met Lynne on a blind date at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln. Our first visit together to her family cottage on Fairoaks Beach was in the summer of 1964, shortly before we were married.

Gerks, of course, was sold years ago and redeveloped as single-family residences and condos. The condos were among the earliest on West Lake. The craze has grown in recent years and seems as though it may be running out of control this summer.

Love reading the history of Okoboji...and of the family names that were so familiar...a long time ago. Thank you for that!