Political Polling: Understanding what the numbers really mean and don't mean

The public opinion polling business originated in Iowa nine decades ago when the son of a Jefferson dairy farmer set out to help his mother-in-law get elected to a statewide office in Iowa.

George H. Gallup was born in Jefferson, Iowa, in 1901, the son of a dairy farmer. He became interested in newspapers and journalism while in high school, and carried that interest with him to the University of Iowa, where he served as editor of The Daily Iowan. He concluded his studies at the University of Iowa with a Ph.D.

From there, he went to Drake University in Des Moines as head of the Department of Journalism. His next stop was Northwestern University in Chicago as a professor of journalism and advertising, followed by a position as director of research with a major advertising agency in New York City.

His introduction to public opinion polling came in 1932 when he set out to help his mother-in-law, Ola Babcock Miller, who was running as a Democrat for Secretary of State in Iowa. With Franklin D. Roosevelt running against the Republican incumbent, Herbert Hoover, for president in the midst of the Depression, it was a good year to be a Democrat. Roosevelt won, and so did Gallup’s mother-in-law.

Another big winner, however, may have been Gallup, himself, who became fascinated with a new-fangled idea: scientific public opinion polling. His big idea was that if you control the polling sample so that it accurately reflects the total populace in terms of key demographics, especially gender, age, and location of residence – income and education controls would come later – the opinions of a few would be essentially the same as the opinions of the whole. It has been compared to sampling a spoonful of soup to know how the whole pot of soup will taste.

Gallup started his own polling company, the American Institute of Public Opinion, in 1935. The following year, he won national recognition with a scientific poll that showed Roosevelt leading in his run for a second term against Republican Alf Landon of Kansas. Meanwhile, the non-scientific mail-in presidential preference poll conducted by The Literary Digest in 1936 erroneously predicted a win for Landon.

Gallup’s approach to polling would become the future, and the American political landscape would be forever changed.

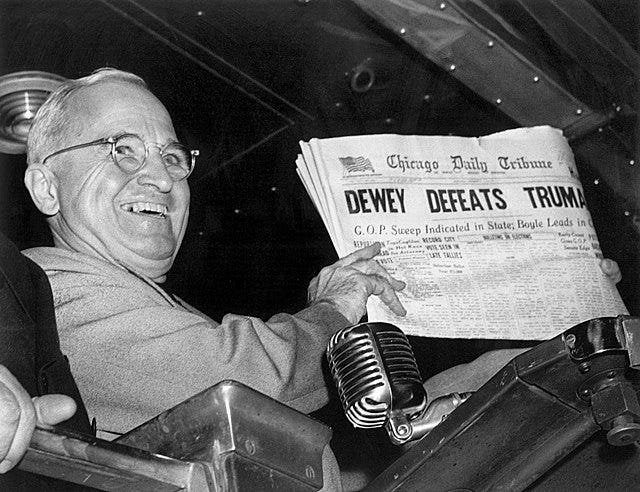

For every election, Gallup would send his interviewers into the field to knock on the doors of residences in randomly selected blocks. Amazingly the system usually worked. Except in 1948, when Gallup’s last poll before the presidential election showed Governor Thomas E. Dewey of New York leading President Harry S Truman. Truman defeated Dewey in a memorable election that was not decided until after the Chicago Daily Tribune called it wrong on election night with a “Dewey Defeats Truman” headline across the top of Page 1.

Gallup quickly realized that he had made a mistake in conducting his last poll three weeks before the election. Opinions and voting preferences can change in the final weeks leading up to an election, especially in a close race. In the future, he and other pollsters would continue polling up to the weekend before Election Tuesday.

The lesson was a reinforcement of one of the universal truths about election polling: Every public opinion poll is no more than a snapshot of a minute in time – an indication of how voters are leaning at the moment the poll is conducted.

It is a lesson we seem to be forgetting again today. The manner in which poll results are presented by much of the media today suggests that a particular poll of the moment is a prediction of who will win the election. Even the Gallup website today describes the work of the company’s founder as “election forecasting.”

An election poll, however, is never more than a snapshot in time. Especially today – in a media and technology world where new information flashes instantly and constantly, always working to move votes one way or the other.

It can be argued that the only real value of early polling in today’s fast-moving world is to provide insight for political operatives, information that can be used to develop strategies designed to reinforce or to overcome whatever the polling result shows at a moment in time.

There are other problems in polling today.

One is that every poll has a margin of error, which varies based on sample size. The smaller the sample, the larger the margin of error. Beyond that, however, recent research has suggested that polling margins of error may be affected by other factors as well. The result may be that the margins of error are significantly and routinely understated.

The New York Times reported in 2016 that typical stated margins of error for larger-sample polls may be as large as 7 percentage points, rather than the 3 percent points, which often is stated. However, the public needs to remember that a 7 percentage point margin of error means that the support shown in a poll for each candidate could be off by as much as 7 percentage points. Which means that the error range could be as much as an astounding 14 percentage points.

Then, there is a more recent and evolving significant issue in the polling world regarding the way information is gathered about peoples’ opinions.

Remember those early days of polling referenced above? When George Gallup sent real people out to interview real people? The poll taker stood at the door, facing the respondent, asking questions, and recording the answers.

Gallup did it that way for a couple of reasons. One was that the alternative, the telephone, was hit-and-miss in the 1930s. Not every household had a telephone by a long shot, so it was hard to draw a telephone sample that statistically reflected all of a particular community. Also, there was a higher probability of getting honest answers from someone the interviewer was looking in the eye.

Over the years, as telephones became omnipresent in American homes, the pollsters converted to that means of contact – primarily because it was cheaper and quicker. * The sample mix still was accurate, but the percentage of honest responses may have slipped a bit. It’s easier to try to skew a polling result to lean a certain way when the respondent is answering questions over the phone than it is when the respondent is facing the interviewer. Still, the polling system pretty much worked.

*Footnote: There’s an adage in polling. Every time an organization conducts a poll, the goal is speed, quality, and cost control. In polling, however, you can only have two of these. Pick any two of them, but it is impossible to have all three.Today, however, households with landlines have fallen into the minority. Everyone has a cell phone, so that is how polling results must be obtained. The problem is that a lot of people only answer cell phone calls from numbers they recognize. Polling companies may have to call 10,000 cell phone numbers to obtain a 1,000-person sample.

There is a built-in problem in this situation. How can pollsters be sure that people who are not inclined to answer cell phone calls from unknown numbers don’t disproportionately share particular points of view on certain issues or candidates – views that then become under-represented in the polling result?

Maybe the reason a lot of people do not answer unknown calls is that they are too busy. The result would be that the polling sample would be overweighted with people who have all kinds of time on their hands. If so, would that make a difference in the polling result? The answer is that no one knows for sure, but doubts, at least, exist – especially given the relatively large number of polls that were wrong in the two most recent presidential elections, 2016 and 2020.

The bottom line here is that polling results must be read very carefully. We also might all do well to avoid becoming too excited or too disappointed by the hundreds of polling results that will become news between now and November 5. Election day is the only poll that counts.

Arnold Garson was a co-author of polling questions and news articles reporting poll results for The Des Moines Register’s Iowa Poll in the 1970s and ‘80s. His partner in this assignment was the late James Flansburg.