The things you never knew about Jewish Iowa

The story of a randomly selected handful of Jews who played important roles in shaping the state of Iowa and some of its cities during the state’s early years.

The first official white settlement in what would become the State of Iowa began in June 1833, following the Black Hawk War – a year-long skirmish between the Indians of Eastern Iowa and the Illinois Militia.

The Indians ultimately surrendered, but the Federal Government also required them to open for American settlement a 50-mile-wide strip of land along the west side of the Mississippi River. The strip ran about 200 miles north from the Missouri border.

Alexander Levi, Iowa’s first Jew

Levi wasted no time in getting to the newly opened unorganized territory. He was born in France in 1809 with ancestry that traced back to the Sephardic Jews of Spain. He immigrated to America at age 24 in 1833, arriving at New Orleans. He appears to have proceeded north with other pioneers via the Mississippi River to the northern tip of the newly opened territory.

He arrived there on August 1, 1833, within two months of the time the strip of land had become available for settlement by the U.S. The fledgling community that would evolve at that location would be named for the French-Canadian fur trader, Julien Dubuque, who began trading with the Indians there years before the U.S. acquired the land through the Louisiana Purchase.

Upon arrival, Levi opened a small grocery store. It was the first grocery store in Dubuque, which, in turn, was the first city in Iowa; also likely the first grocery store in Iowa, which would not be fully opened for official settlement for another five years. The store was situated at the corner of Eighth and Main Streets.

Levi wanted more than a grocery store, however. He also would come to own and operate two mining businesses and serve as Justice of the Peace.

One of Dubuque’s most notable citizens through its first 60 years of existence, Levi also was the first foreign-born Iowa resident to become a naturalized citizen of the United States.

It happened one day in 1837 when Iowa was still an unnamed part of the Wisconsin Territory. Levi and several other foreign-born residents of Dubuque decided to travel to St. Louis, the nearest city where they could become naturalized citizens. The trip was about 350 miles downriver from Dubuque.

The group arrived at the U.S. government office where citizenship applicants were being processed – probably a courthouse. The group formed a line and Levi took a position as the second man in the line. The man in front of him, however, was uneasy, having no idea how the process worked. He sheepishly asked Levi to trade places with him so he could watch before he had to experience it himself.

Later research would show that Alexander Levi was the only Jew in America to become Naturalized-U.S.-Citizen No. 1 of any state in the country.

William Krouse, the first Jew in Des Moines

Krouse was born in Germany in 1823 into a Jewish family that was able to provide fine educational opportunities, despite meager resources. A brother, Robert, came along nine years later.

Together, William, 19, and Robert, 10, seeing the German Revolution on the horizon, left for America in 1842. They settled in New York City, where William set out to earn a living for the two of them as a peddler. It was a common first job in America for immigrant Jews without money.

It required few resources – a horse, wagon, and some inexpensive household goods that could be obtained, often second-hand, for little money. Also, it avoided seeking employment in an established business, where the operator, almost always a non-Jew, would likely require all employees to work on the Sabbath and Jewish holidays. Peddlers set their own hours and workdays.

William appears to have been highly successful. He learned the language quickly and had a natural gift for building friendships. In 1848, after about 6 years working as a peddler on the streets of New York and setting aside money for their second act, the two brothers set out together for middle America, location to be decided.

Somehow, they stumbled into Iowa, which had become a state just two years prior, settling in an unknown place called Raccoon Forks, situated in south central Iowa at the confluence of the Raccoon River and Des Moines River. Krouse said that when they arrived, “I don’t think we could have more than 15 or 20 people.”

By most counts, it was “a deserted spot, possessed of everything but favorable prospects for a large city,” according to a 1905 reference work.

Still, Robert Krouse, who seemed to have natural leadership skills, decided that “he could make something out of the forsaken hamlet,” according to the 1905 book, “The Jews of Iowa,” by Rabbi Simon Glazer.

Krouse departed for a larger city, unnamed, possibly Chicago or St. Louis, acquired a stock of goods, and returned to the excited villagers to sell his wares and live among them. Within a short time, “we organized and made a town of it and called it Fort Des Moines. From that time on, we commenced to grow very rapidly,”

First, Krouse, who was single at the time, became the founder of the first public school in Des Moines, and, by extension, the Des Moines public school system.

Then, understanding the importance of religion in building a foundation for a thriving city in 19th century America – but being among only a handful of Jews in Des Moines – Krouse became what he described as a “liberal contributor,” to fund drives for the construction of the first Methodist, Presbyterian, and Catholic churches in Des Moines.

Finally, Krouse became a key figure in what was to be Des Moines’s big play for growth and recognition. It must have seemed little more than a dream at the time. Krouse and four other men from the settlement – Hoyt Sherman, Judge McKay, Dr. Brooks, and a Mr. Berkley – formed a committee that set out to travel the state and lobby the Legislature beginning in 1849 to move the Iowa state capitol from Iowa City to Des Moines. Krouse’s role was described as “the projector, or one of the projectors” in driving the effort, according to the 1905 book about the Jewish history of Iowa.

Five years later, it happened. The General Assembly decreed that the state’s capitol building be moved to a location “within two miles of the Raccoon fork of the Des Moines River.”

The Younker Brothers

Jewish settlement in Iowa grew slowly. By 1860, the population of the state had grown to 675,000, while the Jewish population totaled around 500; roughly seven Jews for every 10,000 residents. Though small in numbers, their presence was outsized.

The 500 Jews of Iowa in 1860 may have translated to around 150 families spread throughout the state. There was not yet any location of residence in Iowa where a minyan – the 10 men age 13 or over needed to commence a worship service – could be gathered. Meanwhile, an inventory of Jewish-owned Iowa businesses up to that time lists 103 commercial establishments situated in 35 different cities. The overwhelming majority of these businesses were retail clothing or dry goods stores. (The inventory appears to include any business that was operating for even a short time prior to 1860.)

During Iowa’s early years of official settlement, beginning in the mid-1830s, the first disembarkation point in Iowa for northbound travelers via the Mississippi River was Keokuk. That may explain, in part, how Keokuk came to be the third-largest incorporated city in Iowa in the first censuses after statehood, 1850 and 1860.

By 1870, Keokuk had 12,000 residents and was the same size as Des Moines. It also had the largest Jewish population not only in Iowa, but also, of any city in Minnesota, Nebraska, Kansas, or Colorado, according to a 1941 book, “A Century of Iowa Jewry,” by Jack Wolfe.

It was the beginning of the so-called Golden Age of Jewry in Keokuk, and it continued into the mid-1890s.

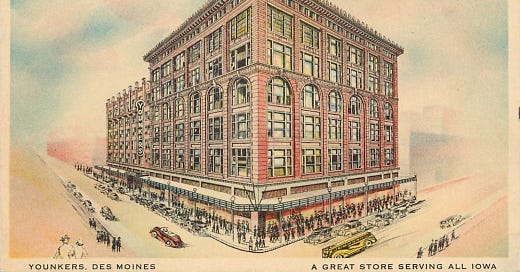

By far the most notable commercial venture in Keokuk during this time was Younker Bros. clothing and dry goods store. Many have heard pieces of the Younkers’ story, which has been told often and well. The short version is that it rose to become one of the largest and most successful retailing businesses in the Midwest. But the best telling of the story comes straight from Marcus Younker, one of the three founding Younker brothers:

“I was born in Lipno, Poland . . . in August 1839, and like all the rest of the boys of that town, I attended Hebrew School till I was Bar Mitzvah. But as there was no profitable field of labor or any other enterprise open, neither for any of my brothers nor myself, we concluded to come to America. Thus, my brothers and I came to New York in 1854 to hunt our fortunes.

“I had a stock of stationery amounting to $2.50 to start my career in this country. But my sad experience of my first day’s adventure is forever imprinted on my memory. I was to take a stage to Union Square, where I was to search for trade either on the street or by ascending and descending countless steps leading to offices. But as I was getting on the stage, my entire stock fell into a dirty gutter and there my tearful eyes saw how my whole fortune perished. Kind-hearted bystanders had remorse upon me and helped me out with the sum of one dollar and that . . . was my start in the United States.

“We came to Keokuk in 1856, where we started a small business, but . . . some of us, sometimes myself, and sometimes my brothers . . . [Samuel or Lipman] would go out and ramble through the country and peddle among the brave and generous pioneers of Lee and Des Moines Counties. In 1885, we found ourselves too large for Keokuk. Our business had outgrown the town, which at that time, along with all the other riverfront towns, was on the decline. Ever being ambitious to attain a firm foothold in the business world, we took out $6,000 of our capital and invested in a branch store in Des Moines, which was said to be the promising center of commerce in Iowa. That our investment was profitable will be believed by all Iowans.”

Wow.

The one missing piece of the story is that the youngest of the four brothers, Herman, had gone to Des Moines in 1874 to start the first Younkers store there. Samuel died in 1879 and the three surviving brothers reunited in Des Moines as the business grew. Lipman and Herman ultimately relocated to New York to manage related aspects or parts of the business from there. Marcus continued to operate the Des Moines store until his retirement in 1895; he died in 1926.

The following year, Younkers would complete the foundation of its business empire, merging with Harris-Emery, the last large competing local department store in Des Moines.

The Rothschilds – but which Rothschilds?

Rothschild family members who settled in Muscatine and Davenport may or may not have had distant ties to the Rothschild family of worldwide financial fame.

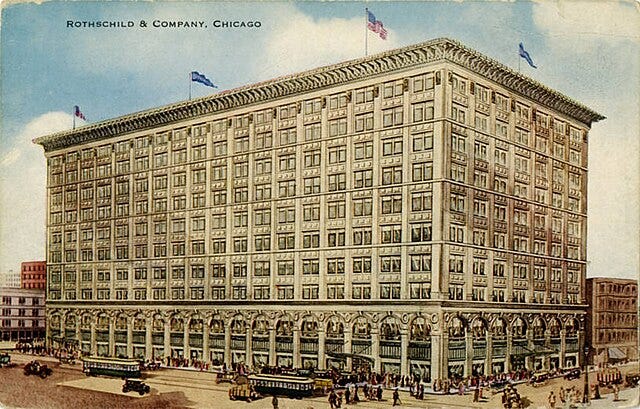

It is known for sure, however, that the brothers Emanuel and Abram Rothschild and their uncles, coming from families of modest means in Germany, created and operated retail businesses that gathered elite-level wealth in Davenport and Muscatine before the brothers moved on to become power brokers and acquire more substantial wealth in Chicago.

Emanuel Rothschild had arrived in America and gone first to Muscatine to live and work for his Rothschild uncles there in the city’s largest general store. Later, David Rothschild, one of the uncles, would operate the D. Rothschild Grain Co., in Davenport, one of the largest grain dealers in the region. Emanuel soon opened his own retail clothing store in Davenport.

Emanuel’s younger brother, Abram, arrived in 1868. He began clerking in his brother’s Davenport store and going to school at night to learn the language. Soon, Emanuel invited Abram, still a teenager, to join him in operating the business. The name of the store was changed to Rothschild & Brother. It became one of the city’s dominant clothing retail businesses.

All of which brings us up to the year 1871 and the Great Chicago Fire, 175 miles northeast of Davenport.

The City of Chicago was devastated. The brothers Rothschild were excited: Opportunity was calling them.

First, Emanuel and Abram established a small retail clothing store in downtown Chicago. It did little more than establish without doubt that the brothers had underestimated the opportunity to prosper in the wake of the fire.

Their next step was to open a clothing factory in Chicago to supply their store. They soon moved the business to larger quarters. They also decided to abandon their business interests in Davenport; going forward, they and all of their business holdings would be based in Chicago. They moved their manufacturing business twice more to larger quarters.

Then, they incorporated it and established locations for it in several large cities of the West.

By the early 1890s, Abram’s business reputation was such that he was asked to become a director of the entity that was planning the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, aka The World’s Columbian Exposition. He also became a director of the Chicago Stock Yards and a major Chicago bank.

Then, he had another idea. He would build and operate one of Chicago’s largest department stores of the time; the A. M. Rothschild & Company Store would be a full block long and 10 stories high. It would employ 2,000 people. By the 1900s, Abram’s various businesses would make him a millionaire; in today’s terms, it would translate into the billions.

How did this story end? Not happily. Abram committed suicide by gunshot at his home in Chicago in 1902 – in part, because he was troubled and embarrassed by a serious construction remodeling accident at his department store that resulted in substantial financial losses. The store was sold to Marshall Field in 1923.

Dr. Arthur Steindler, a big name in America in orthopedic surgery

Arthur Steindler, a native of Czechoslovakia, was a world-renowned orthopedic surgeon at the University of Iowa, acknowledged as one of the greatest orthopedic surgeons of his time.

He graduated from the University of Vienna in 1902 and immigrated to America in 1907. He joined the faculty of the University of Iowa in 1912 to become the founder of the Department of Orthopedic Surgery at the university’s College of Medicine.

He developed an international reputation, personally caring for more than 70,000 patients, many crippled by polio, scoliosis, or congenital deformities. He wrote more than 130 papers and nine books about orthopedic surgery in several languages, being fluent himself in seven languages.

He served as president of the American Orthopedics Association in 1933. From his base at a Big 10 university in a small midwestern city, his influence spread throughout the world.

He died in 1959, but the orthopedic clinic that bears his name today has offices in Iowa in Muscatine, Washington, Burlington, Iowa City, Fairfield, and Williamsburg.

A story about popcorn

A. H. Blank came to America at the age of 8 and four years later, in 1890, was in his glory hawking balloons at Omaha’s Trans-Mississippi Exposition.

Though still a young boy, he knew he loved the excitement and glamour of show business.

It seemed a natural evolution when, in 1912, he and a partner stumbled their way into opening the first motion picture house in Des Moines – transforming a vacant Locust Street storefront after removing the interior partitions. An electric piano and a wobbly stand-up screen completed the scene.

But Blank never seemed happy with the status quo. He soon moved on to a more elaborate venture – a screening venue with an electric organ, a small orchestra, upholstered seats, young boys working as ushers, and newspaper advertisements to promote his films.

He opened theaters in Davenport, Cedar Rapids, Omaha, and elsewhere.

He established a sizeable fortune, allowing the establishment of facilities for the public benefit that would extend his name far into the future – the A.H. Blank Children’s Zoo in Des Moines on the former site of Fort Des Moines and the Raymond Blank Memorial Hospital for Children in Des Moines in memory of their son, Raymond.

The Blank theaters were acquired by a new owner in 2002. There is one thing about A. H. Blank and the theater business, however, that likely will carry on as long as movie theaters exist. A. H. Blank was the first theater owner/operator in America to come up with the idea of making and selling popcorn in his theaters.

Theater owners/operators have reaped millions of dollars from his idea.

Sources for this column include but are not limited to: A Century With Iowa Jewry by Jack Wolfe, Copyright 1941, Iowa Printing & Supply Co., The Jews of Iowa by Rabbi Simon Glazer, Copyright 1904, Koch Brothers Printing Co., Des Moines, History of Iowa by Dorothy Schwieder, Iowa State University, Iowa Official Register, Gallery of Local Celebrities, No. LXXIII, Abram M. Rothschild, Chicago Tribune, June 23, 1901, Arthur Steindler: Founder of Iowa Orthopaedics, by Joseph A. Buckwalter, M.D., The Iowa Orthopedic Journal, Volume 1, Number 1, A. M. Rothschild Takes His Life, Chicago Tribune, July 29, 1902.

NOTE TO READERS: I write this column, Arnold Garson: Second Thoughts, as a member of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative. You can subscribe for free. However, if you enjoy my work, please consider showing your support by becoming a paid subscriber at the level that feels right for you. Click on the Subscribe button here. The cost can be less than $2 per column.

Iowa Writers Collaborative Roundup

Linking readers and professional writers who care about Iowa.

These are fascinating stories, Arnie! Thank you so much for researching and sharing.

I love these stories. Thank you for taking the time to tell them. I always learn so much and I love to share them.