The Downtown Department Store: A Remnant of the Past and Where It Came From

Bonus item: A brazen downtown daylight robbery in my hometown. My mother mouths off to the perp.

For much of the 20th century, the downtowns of America were anchored by giant department stores.

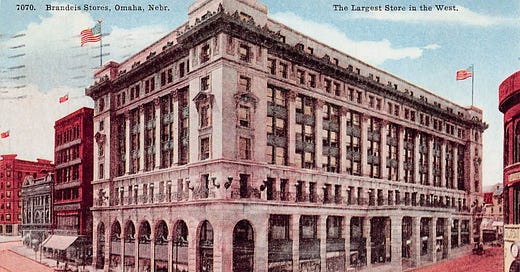

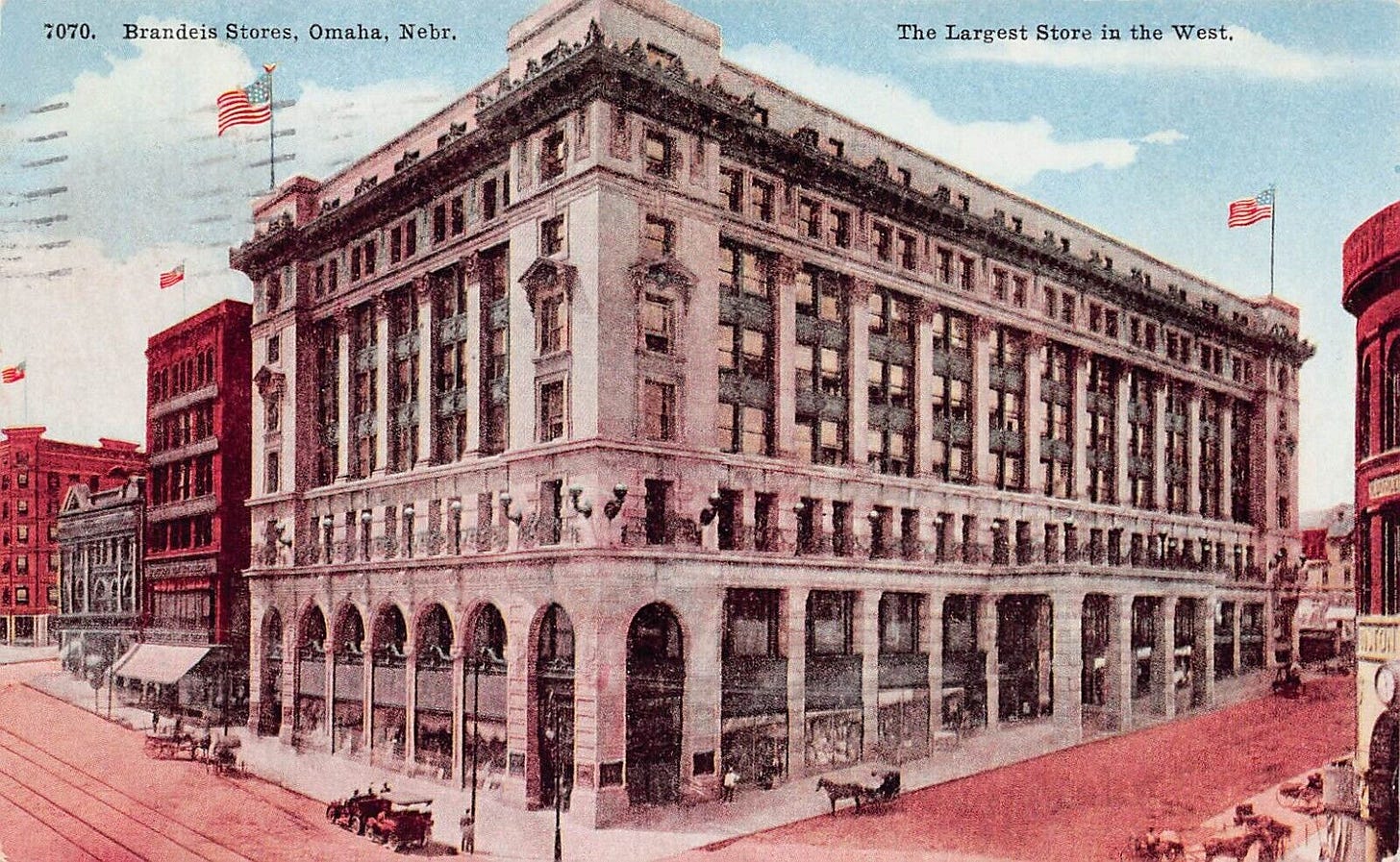

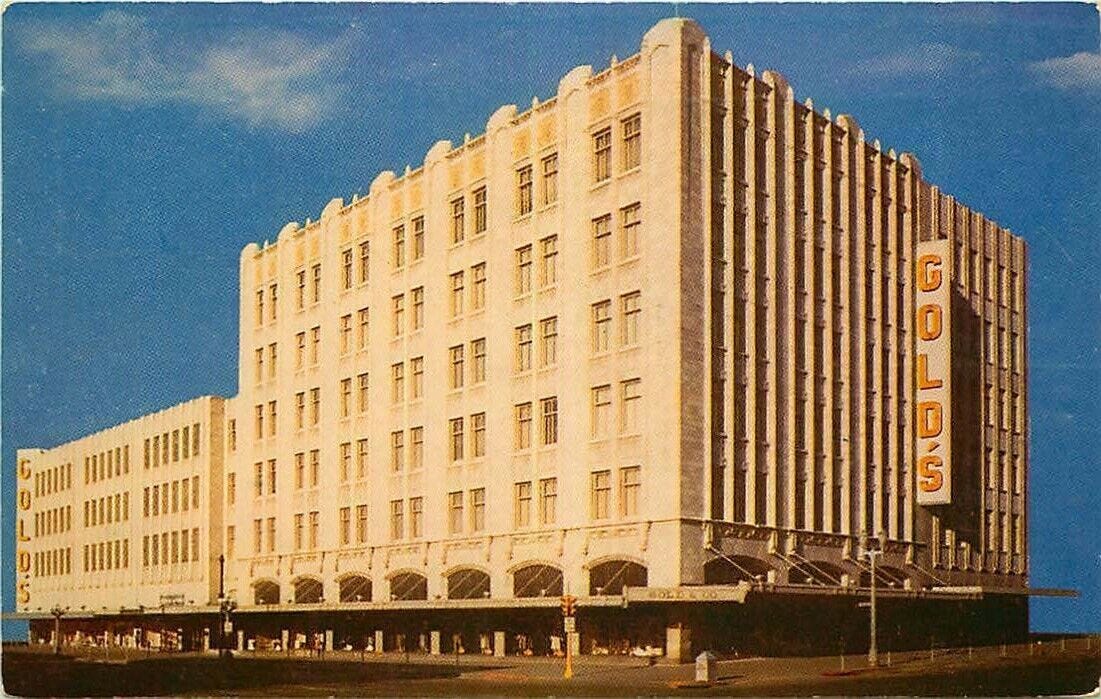

Every city of consequence had a department store: Younkers in Des Moines, the People’s Store in Council Bluffs, J. L. Brandeis & Sons in Omaha, Gold’s in Lincoln.

Everyone shopped for everything in those stores.

There also was a little-discussed oddity about these stores. They were disproportionately owned and operated by immigrant Jews and their descendants. Although Jews accounted for no more than about 1 percent of the population of America during these years, they were the founders and operators of downtown department stores across the country. Even in the Midwest, where relatively few Jews lived, Jews owned and operated many of the downtown department stores.

The phenomenon has been written about periodically over the years, but the key question rarely has been addressed: How and why did this come about?

The answer is both simple and complicated. Like much else with the Jews, the root cause was anti-Semitism. But that root was planted long before the Jews immigrated to America. It was, first, the anti-Semitism of Eastern Europe that confined many of the world’s Jews to an area known as the Pale of Settlement in Western Russia. Occupational choices were limited by law within this area. One of the few occupational opportunities for the Jews was to become artisans. They made things – clothes, candles, soap, necessity items – and sold them out of their homes or from a booth in the town square. In effect, they became shopkeepers; retailers, but with very limited inventories and very low costs.

When Jews started coming to America in large numbers, in the 1880s, they discovered that the American workplace, not surprisingly, did not accommodate Jewish customs – specifically, keeping the Sabbath and not working on the Jewish holidays. It was another form of anti-Semitism. However, as the Jews often did, they found a way around it. If they wanted to set their own work schedules, they would need to be self-employed.

Many of them, thus, discovered the life of a peddler. They needed little money to acquire a horse, a wagon, and a few household items for merchandise. They traveled widely and made a living. But it was hard work, and often kept them away from home.

Louis Krasne, a Jew from Poland who settled in Fremont, Nebraska, in 1888, started this way. Louis (a first cousin of my great-grandfather, Wolfe Krasne*) was peddling his wares with two of his sons, Ike and Herman, in Fullerton, Nebraska one day in 1897 when his horse died. Caught in a jam 85 miles from home, Louis rented a storefront in Fullerton, moved his merchandise inside, and began advertising in the local newspaper. Krasne’s Store was born; a huge success from the beginning. He soon moved his family to Fullerton, a town of about 1,400.

A decade later, two of his sons got a bigger idea. They joined with some other family members to purchase a retail store in downtown Council Bluffs: The Peoples’ Store, which soon became the city’s anchor department store. The family eventually closed the store in Fullerton (after an anti-Semitic incident in which the storefront was emblazoned with hate messages) and consolidated in Council Bluffs, where they and their descendants operated The Peoples’ Store for 65 years.

* Wolfe Krasne, also from Poland, was responsible for keeping order at the inn his father operated in Bielsk, Poland. The inn was frequented by Russian soldiers, who often drank too much and became rowdy. There was a confrontation one evening. Wolfe, a large, strong man, survived. The drunk Russian did not. That night, at the urging of his family, Wolfe left Poland for America. Leaving his wife and children behind, he sneaked away in hay wagons to the border and arranged passage to the U.S., probably from Hamburg, Germany. His wife and children, including my grandmother, would follow eight years later.

Across the river from Council Bluffs, in Omaha, Jonas L. Brandeis, an Austrian Jew, arrived with his family in 1881, after a few years in Wisconsin. Within a few months, he had opened his first retail store in Omaha – destined to become the behemoth J. L. Brandeis & Sons’ department store and ultimately, an 11-store chain.

In Iowa, the Younker brothers, Jews from Poland, had opened the first Younkers store in Keokuk in 1856. In 1874, the youngest of the brothers, Herman, was sent to Des Moines to open a branch there. Five years later, the three older brothers closed their store in Keokuk and joined Herman in Des Moines. This, too, would become a downtown behemoth and the anchor store of a chain that eventually would acquire Brandeis.

In Lincoln, my hometown, William Gold founded a small retail store with a partner in 1902. Gold was from Plattsburgh, New York, where his father, Levi Gold, a German Jew, had settled upon immigration from Germany. Levi’s work: He became a peddler. Young William, born in 1862, began moving westward in his early teens and working his way up in the world of retailing – Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, then Sutton, Nebraska, Hampton, Iowa, and eventually Lincoln, where his retail store was destined for the big time. Within a year, his partner in Lincoln departed, leaving Gold the sole proprietor. By 1924, Gold relocated to a building at the corner of 11th and O Streets, where Gold’s would grow to consume three-quarters of the entire block. William’s son, Nathan Gold, took control of the retail empire after his father died in 1940. Ultimately Gold’s was sold to Brandeis in Omaha.

Not all of these ventures were successful. Another of my great-grandfathers, Louis Stine, and his sons and sons-in-law, purchased a small department store in Lincoln in 1928. Their timing, several months before the beginning of the Great Depression, was not good. The store, The Grand Leader, about one block east of Gold’s, closed in bankruptcy in 1933.

In today’s world of discount and online retailing, the department store has fallen upon hard times. Many of them, including the four aforementioned stores, have closed, and downtown America has changed dramatically.

The People’s Store in Council Bluffs succumbed to urban renewal in 1972. The Brandeis building in Omaha has been converted to apartments. The Younkers building in Des Moines was destroyed by fire several years ago. Most of the giant Gold’s store building in Lincoln was razed recently to make way for a new hotel.

Ultimately, apartments, dining, entertainment, the arts, and locally owned specialty stores with unique products would become the future of successful downtowns everywhere. Department stores and other basic retailing faded from the downtown horizons across America.

* * *

The Gold’s store in Lincoln was a hallmark of my youth. I virtually grew up in a chain-owned specialty store in Lincoln, across the street from Gold’s. My father managed that store, The Big Shoe, from the late 1930s to the mid-1960s. The store was one of hundreds of shoe stores throughout the country operated by a national chain, Schiff Shoe Company. The company also operated retail shoe stores by other names, including the R & S Shoe Stores and Schiff Shoes, at many locations in Iowa -- Des Moines, Ames, Boone, Keokuk, Mason City, Cedar Rapids, Fort Madison, and Waterloo. And yes, the Schiff company was owned and operated by Jews. Chain specialty store retailing of this era was another business through which Jews across the country often profited. For the founders of these chains, the story was similar to how the Jews got started in the department store business.

In Lincoln, The Big Shoe Store was one of several small stores across the street from Gold’s that operated mostly in the shadow of the big department store. They were profitable businesses, but seldom made news or drew much attention.

* * *

And now, a bonus item, a personal story. The 1930s was an era of brazen broad-daylight robberies. One of the most famous of these in Lincoln entrapped my father and mother, though they were not yet married.

It was a Thursday in May 1935, when two men entered Clark’s, a men’s clothing store across the street from Gold’s, about 30 minutes before closing time. They shopped casually until just before the store closed. One of them then pulled a gun and announced a robbery to the nine persons who worked at this or nearby stores; all had gathered at Clark’s for carpool rides home after the 6 p.m. closing. The nine were bound with bailing wire brought by the robbers and rope found in the store. They were tied to a clothes rack while the robbers casually went about their business for about 45 minutes.

One customer who entered the store a few minutes before closing was approached by one of the robbers pretending to be a salesman. He sold the customer a hat for $2.95, escorted him to the exit, locked the door, and pocketed the money. The robbers even provided lit cigarettes to the two victims who wanted them.

The victims included my father, Sam Garson, who had come to Clark’s, operated by his brother-in-law, Dave Davidson, for a ride home. My birth mother, Celia Stine, then Sam’s finance, had come to the store for the same reason. Celia was an assistant buyer for women’s gloves at Gold’s, one of the few women at Gold’s to hold a ranking position in those years. When it was her turn to be tied up, she cried out at one of the robbers: “What is this, anyway? Are you kidding?” To which one of them replied, “It’s the real thing. We’re not kidding.”

The victims, who were not injured, managed to free themselves a few minutes after the robbers left. The take was $261 cash from the victims and the cash register and more than 15 men’s suits. In today’s money, the loss was in the range of $15,000.

The Big Shoe Store opened at 1038 O Street in May 1931. My father, who graduated from high school in Lincoln that spring, applied for a job as an extra sales clerk for the grand opening. He stayed on and worked his entire 47-year career for the Schiff Shoe Co. – in Lincoln, then other cities, and finally in Columbus, Ohio, at the home office.

I sold my first pair of shoes at The Big Shoe Store at age 12 and worked there as a part-time sales clerk, beginning at 35 cents an hour, for 12 years. It was an introduction to the workplace that would provide many lessons for me through part-time positions in Lincoln during college; also after college, through a decent career in newspapering that spanned much of the country.

Thank you, Lincoln, for shaping work habits that would serve me well.

Thank you, also, to the Jews of the Midwest in the early and mid part of the 20th century who blazed trails to success in retailing proving that dreams were possible. My chosen career path was different, but the lessons were not lost on me.

* * *

Celia died suddenly of a stroke in February 1942 when I was nine months old. My father remarried about 18 months later. Some readers may remember his second wife, Dorothy, from my column last week about immigration. In effect, I had two mothers, and they were both important to me. This story about Celia is one of the few extant recollections that survived her. She would speak her mind even as a man held a gun on her.

Learned from this historical review. Sioux City had two downtown Younker stores within a block of each other. Younker Martin and Younker Davidson. The Davidson (yes Jewish) family built a business, remarkable structures and a reputation of excellent service. I grew up in a neighborhood with Jewish families, two synagogues and bagels. Great experience with a variety of cultures, religions, professions, and politics. I learned about DEI before it was a thing. Keep writing Arnold, you have much to share.

Great and vital history! I particularly loved Celia's question to the robbers. Maybe you can also tell us about Nebraska Furniture Mart sometime (though I am sure several writers have tackled that one already)?