Joe Biden’s speech to the Democratic National Convention this week offered a perspective that no other president in American history has been able to provide – a capstone on a record half-century in federal elective office culminating in the presidency.

Among the nation’s 46 presidents, including the 11 vice presidents to have been elected to the presidency, the length and breadth of Biden’s career stands alone – as he put it, literally, first being (technically) too young to serve, then (realistically) too old.

It also has been unusual in at least one other important way.

Though it took some persuasion from his friends and associates, Joe Biden knew when to quit.

At least seven of the 45 presidents who preceded him did not know when to quit. At least seven of the 45 continued to seek an additional term of office after it had become clear that that would not happen, or, in one case, that it should not have happened.

Ultimately, the power of the presidency was so enticing that they could not let it go. At least one was young enough to go on and do exciting things – and did so, but still ended up trying for a comeback. Most of the others could have found useful and important things to do in other arenas. The power to direct, control, or impact the actions of others, however, was simply too seductive.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Unlike George Washington, who declined a third term in office, in part because he knew his health was failing, Franklin D. Roosevelt pursued and won a fourth term despite knowing that he was a dying man.

Roosevelt was diagnosed with a severe cardiovascular illness in March 1944. Soon, he was able to work no more than about 4 hours a day, yet he, his family, and his medical team conspired to keep the seriousness of his illness from the voters in November 1944. He lost only 12 states, including eight states that provided no more than eight electoral votes each – a landslide. Unfortunately, however, he died 102 days after his inauguration for his fourth term. The cause of death was a cerebral hemorrhage brought on by his cardiovascular illness.

It may have been the ultimate example of a president not knowing when to quit. Given that he made no efforts to keep his vice-president in the loop regarding World War II and U.S. relationships abroad, his insistence on a fourth term placed the country at exceptional risk. Harry Truman rose to manage the risk as Roosevelt’s vice-president and successor even though few – probably including Roosevelt – would have predicted that.

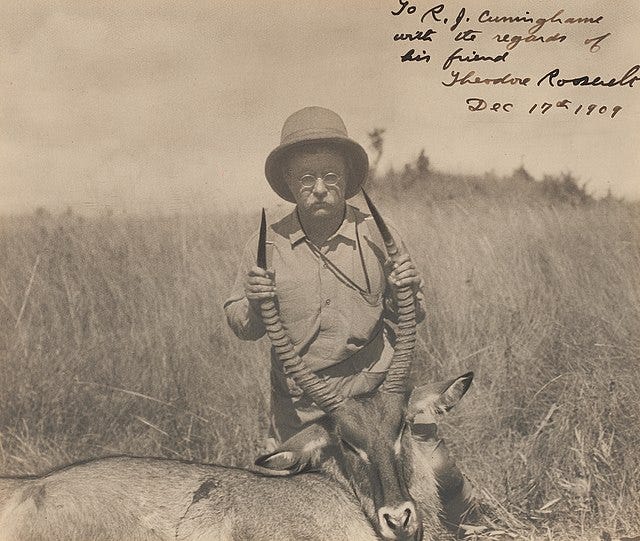

Theodore Roosevelt

Teddy Roosevelt, like Harry Truman, was an accidental president, taking office following the assassination of William McKinley. During his seven-plus years in office – the remainder of McKinley’s term and one elected term of his own – he became one of the most widely admired presidents. He utilized the Sherman Antitrust Act to break up industrial combinations that were seen as restraining foreign trade. He won the Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating an end to the Russo-Japanese War. He created the National Parks system. He facilitated the construction of the Panama Canal.

He chose not to pursue a third term in 1908, choosing instead to crown his successor, William Howard Taft, then the Secretary of War. He then embarked on a 10-month African Safari and tour of Europe.

His mistake came upon his return to America and deciding that despite the excitement of his world adventures, nothing quite compared with being President of the United States. He attempted – unsuccessfully – to win his party’s nomination for President in 1912, then decided to try to retake the presidency with a new third party. Basically, he succeeded only in putting the opposition party in power.

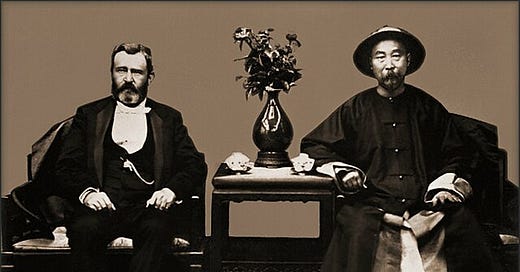

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant presided over one of the most scandal-ravaged presidencies in U. S. history -- no fewer than a dozen scandals involving his administration with countless public officials reaping the riches. It can be argued that Grant really did know when to quit in deciding after two terms not to seek a third term in 1876.

Instead, he and his family embarked with an entourage on a two-year world tour. Despite being hailed as American royalty on his tour stops, he, like Teddy Roosevelt, was not satisfied. For Grant, the power of the Presidency was the ultimate elixir. He worked behind the scenes to gather support for his party’s nomination in 1880 and entered the convention with more votes than any of the other candidates.

Still, he lacked enough votes to win the nomination, and after 36 ballots a dark horse candidate suddenly emerged and took the convention by storm. James A. Garfield won the nomination and the presidency, only to be assassinated six months after being inaugurated.

For Grant, it was his first defeat following a chain of victories that began with winning the Civil War. He next invested in a business that went broke leaving him broke as well. Maybe he should have quit while he was ahead.

Footnote: A third term for Grant would not have turned out well for the country. He would have been gravely ill with throat cancer during much of his last year in office.

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover won the presidency by an enormous 5-1 margin in the Electoral College in 1928. Then, in one of the most dramatic turnarounds in presidential history, he lost the presidency by an 8-1 Electoral College margin four years later.

Many factors caused the devastating Great Depression beginning in 1929, but Hoover’s name became linked with the disaster and his perceived lack of empathy for those most seriously affected did not do him any good.

The handwriting was on the wall for a failed attempt to win a second term in office. Somehow, he failed to read it.

Then, despite a long list of accomplishments in the U.S. and abroad both before being elected President and after, Hoover became overtaken by his desire for another term as what often is described as the most powerful job in the world.

He tried unsuccessfully to win his party’s nomination twice, in both 1936 and 1940.

Three other presidents who could not let go

Earlier in American history, at least three more presidents failed to understand that it was time to quit.

Running unsuccessfully for a second term in office does not necessarily mean that the incumbent was in a hopelessly flawed situation that would prevent re-election. Many one-term presidents ran strong, though unsuccessful, campaigns for a second term. But John Quincy Adams was an exception. He won an extremely close election in 1824 that had to go to the House of Representatives to be decided. He tried for a second term four years later, but when his own hand-picked vice-president flopped over to the camp of his opponent, who was carrying the flag of the opposition party, it should have provided a clue.

Not only did Adams lose to Andrew Jackson by a 2-1 Electoral College margin, but his National-Democratic Party faded away and never won the presidency again.

Not unlike Herbert Hoover, Martin Van Buren, elected in 1836, suffered an economic catastrophe early in his administration, the Panic of 1837. Not surprisingly, he lost a bid for a second term in 1840. Also like Hoover, he appears to have been a slow learner. He tried again in 1844, failing to win the nomination, and in 1848, when his nomination by the offshoot Free Soil Party served only to help elect Zachary Taylor.

Taylor died in office in 1850, making Millard Fillmore the president. Fillmore failed to get his party’s nomination, however, in 1852. A few other vice-president fill-ins for presidents whose terms were cut short suffered similar fates. But unlike the others, Fillmore seemed unable to read the tea leaves. He kept trying. He won the nomination of the Know Nothings, aka the American Party, in 1856 – who apparently knew nothing about how to win an election. Fillmore finished third in the popular vote and won only one state, Maryland, in the Electoral College.

It all looks so obvious a century or two later. Smart men, experienced politicians, who should have been able to see what was coming.

What did Joe Biden have that these men did not have in terms of being able to read the tea leaves?

There may be multiple answers to that question, but one obvious one is his willingness to put his country ahead of his own personal quest for power.

NOTE TO MY READERS: I write this column, Arnold Garson: Second Thoughts, as a member of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative. You can subscribe for free. However, if you enjoy my work, please consider showing your support by becoming a paid subscriber at the level that feels right for you. The cost can be less than $2 per column.

Here is a link to the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative Sunday Roundup, where you can get a compilation of our members’ work published the previous week.

Iowa Writers Collaborative Roundup

Linking readers and professional writers who care about Iowa.

Thanks for the history lesson Arnold! I got fascinated by presidents in early elementary school, with the JFK assassination & Hoover dying a few months later. I also collected the president cards from Cheerios boxes...remember those?

Such a great article, so full of information of which I was unaware. Now you have me delving into research on many fronts. Thank you so much for this.