This is the story of two Holocaust survivors, Joe Alexander of Los Angeles and David Wolnerman of Des Moines.

David Wolnerman, the last Holocaust survivor in Iowa, died a few weeks ago at age 96. More about him later.

Joe Alexander at 100 and known by all as Joe is still going strong, traveling the world and telling his story. I met him Wednesday night in Sioux Falls.

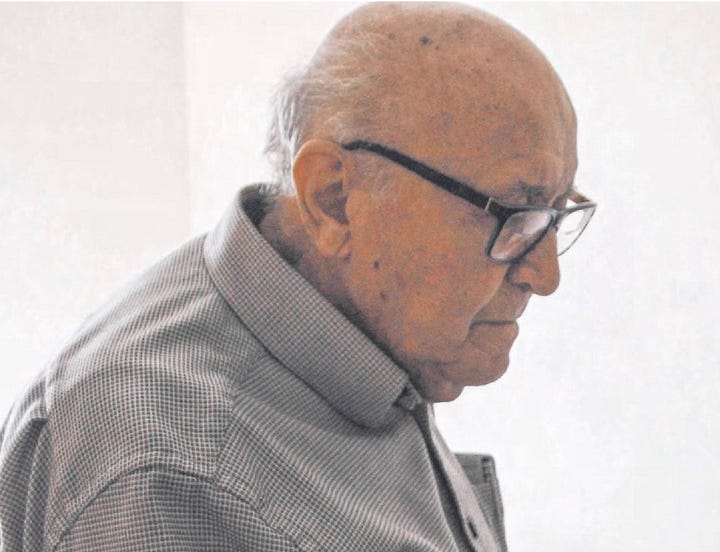

Arnold Garson, left, with Joe Alexander as he prepares for his appearance in Sioux Falls; Joe is wearing a headset microphone on his right side.

Joe was 10 years old, living with his family in Poland, in 1933, when Hitler, just 7 weeks into his new job as Chancellor of Germany, opened the infamous Dachau concentration camp. Joe did not know it then, but he would be imprisoned there someday.

But in 1933, Joe’s life, in a small town in central Poland, seemed a long way from Germany. His father operated a store in the front part of the house in which the family lived, selling men’s work clothes and underwear. “We had a nice, comfortable life,” Joe said.

It was about a week before Joe’s 16th birthday when Hitler ordered his army to attack Jewish homes, businesses, and places of worship across Germany. Many of the synagogues would be destroyed by fire. Tens of thousands of Jewish men were arrested on the night to be remembered as Kristallnacht, the night of broken glass, November 9-10, 1938.

Joe was still 16 on September 1, 1939, when Hitler invaded Poland marking the official beginning of World War II. It was a gradual, but steady downhill slide for Joe and his family s they tried desperately but unsuccessfully to remain out of the reach of the Germans.

First, the family relocated to another small town in central Poland, then Joe was assigned to work in a forced labor camp six days a week, with one day back at home. He contracted blood poisoning and after four or five weeks refused to go back. By October 1940, Joe and his family were relocated and confined to the newly opened Warsaw Ghetto – along with 500,000 other Jews. Joe described the conditions as horrible.

Joe and two of his siblings escaped briefly, but Joe soon was taken by the Germans again and would serve the remainder of the war in concentration camps, including Auschwitz, where, upon his arrival, he would employ some clever maneuvering to escape assignment to the gas chambers by Hitler’s monster of the camps, Joseph Mengele. Joe sensed that with all of the arrivals being assigned by Mengele to one of two groups, he ended up in the wrong one, mostly people who were sick or elderly. As the cover of darkness arrived, he sneaked around the back of the groups from one side to the other, managing to transition from the group destined for the gas chambers to the group destined for hard labor.

Left, the wall of the Warsaw Ghetto from the German side. The wall was 8-10 feet tall, constructed of stone or brick with concrete, and had barbed wire strung across the top. Right, the interior of a gas chamber at Auschwitz. Photos from Wikimedia Commons.

The boy who was 16 when he first met the Germans was a man of 21 when he was liberated as a wave of American tanks and foot soldiers arrived at Dachau on May 2, 1945. His parents and five siblings – four older than Joe, one younger – had been murdered.

His life, thus, started over at age 21, with its next major phase not to begin until 1949, when he finally arrived in the United States.

After a brief stay in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Joe relocated to Southern California, where he has lived ever since. For the past 25 years or so, he has traveled almost full time – in recent years, accompanied by his girlfriend, Reva – telling his story. Wednesday evening, he was in Sioux Falls for a public appearance. He talked nonstop for 40 minutes, telling his story, then engaged in a Q and A conversation for another 20 minutes.

The most powerful moment of the evening came when he stood, walked to the front edge of the stage in a room where 3,000 people were silently absorbing his story, rolled up his left sleeve, held up his left arm, and displayed the number 14284, the tattoo forced upon him when he arrived at Auschwitz. Joe stands something like 5 feet, 2 inches. He seemed 7 feet tall at that moment, having risen above all that Hitler and the Nazis could throw at him in 12 different concentration camps over almost six years.

Joe shows his tattooed left arm to the 3,000 people who attended his presentation in Sioux Falls. His number, 14284, was his name in Auschwitz. (The headset microphone did not work. He had to switch to a hand-held.)

* * *

It is a tragic reality today that the world’s Holocaust survivors are fast disappearing. It can not be helped because life is a time-limited experience.

David Wolnerman died six weeks ago in Des Moines.

He shares some remarkable parallels with Joe Alexander. Wolnerman, too, survived a selection by Mengele, was liberated from Dachau, and spent time at an unusually large number of labor concentration camps.

Wolnerman, according to his obituary in The Des Moines Register, was so ill upon his liberation, that he had to be nursed back to health by Catholic nuns, one spoonful of oatmeal at a time. He, like Joe, finally made it to America – in 1950. He and his wife settled first in Cleveland, where he worked as a pressman for a book publisher. But he wanted to be his own boss. Ultimately, he and his sister, Bluma, and their spouses opened a supermarket in Gary, Indiana. Upon retirement, Wolnerman and his wife, Jennie, relocated to Des Moines, where their sons, Allen and Michael, lived.

Wolnerman, too, had a number tattooed on his arm at Auschwitz – 160344. Significantly, the numbers added to 18, which has a special symbolism in Judaism. The tenth letter and the eighth letter of the Jewish alphabet together spell the word chai, the Hebrew word for life, and the Jewish symbol for life.

Left, David Wolnerman, Des Moines Register photo. Right, the two Hebrew letters (read from right to left) that make up the word Chai, meaning life. The letters, in silver or gold, often are worn as jewelry on a necklace.

Wolnerman lived in Florida for a time. One day at an event, he encountered a man, The Register recounted in another story. They exchanged pleasantries, and the man told him his voice sounded familiar. “Is your name David?” the man asked. Wolnerman said it was, but turned and departed quickly, frightened by the familiarity indicated by a man he did not recognize.

“Come back here, 18,” the man called. Wolnerman stopped cold, suddenly realizing the man had been the older boy with him in a concentration camp, someone who had been a father figure to him. Wolnerman returned to him and they began talking – but not about the past; about the future.

Wolnerman’s primary work in his later years was to educate people on forgiving, but not forgetting, work that continues after his death through an organization maintained by his son and daughter-in-law through the Michael and Missy Wolnerman Holocaust Education Fund.

* * *

David Wolnerman and Joe Alexander spent much of their later years trying to extend Holocaust remembrance for the future. But as the voices of the survivors decline in number every year, an inexplicable growth of both Holocaust denial and anti-Semitism has arisen. We must all listen while we can.

Note to readers: It had not been my intention to begin my work as a Substack columnist in the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative with three columns about Jewish life and death. It just happened that events of the past two weeks have pointed me in that direction. If you are looking for something different, please stay with me; it will be coming soon. Still, if you like these columns, let me know. I would like to get a fix on that.

The Iowa Writers’ Collaborative

Have you explored the variety of writers in the Iowa Writer’s Collaborative? They are from around the state and contribute commentary and feature stories of interest to those who care about Iowa. Please pick five you’d like to support by becoming paid. It helps keep them going. Enjoy:

Keep writing! I appreciate your professionalism and excellent thinking. My children, raised in Des Moines, spent many summers in Israel with their grandparents who walked across Europe after a pogrom in Poland killed their parents and settled in Palestine, becoming Israelis after 1948. My son is a former IDF officer who has luckily aged out as a reservist. We remain hopeful that the guns and rockets will cease, the hostages will be returned, and the innocent people on both sides can rebuild their lives and live in peace.

These columns are fascinating, and I know other topics you tackle will be, too. The path is yours to shape.