The secrets our ancestors took to their graves

There never has been a better time to search for the skeletons in your closet

My roots in America trace back to the four married couples who became my great-grandparents after arriving in the U.S. from Eastern Europe in the 1880s and ‘90s: The Garsons, Greenstones, Krasnes, and Stines.

They came to America because much about their lives in their homelands had become intolerable.

For those who lived in Russia, conscription — for terms of up to 25 years — was a virtual death sentence for young Jewish men. In Poland, Austria, Hungary, and other Eastern European countries, Jews were forced to live in designated neighborhoods and forbidden to own property in most circumstances. Pogroms, primarily in Russia and Poland, struck randomly, leaving death and destruction strewn through Jewish neighborhoods. Finally, throughout Eastern Europe, severe poverty was a common denominator among all Jews during these years.

But as I began digging more deeply into the lives of each of these four couples, I discovered that each of their situations was unique. Each family was driven by different primary factors in making the decision to emigrate, and each of them encountered different circumstances as they settled into new lives in America.

A life-changer in 1889: Eight of their 11 children died in infancy

Barnet and Sophia (Garmise) Garson had been married for 30 years in 1889, when they sent their eldest son, Jake, to New York. The family lived in Minsk, and Jake, at 22, was a prime target for the Russian Army. He needed to get out of Russia ASAP. The plan appears to have been for Jake to begin learning the language and making connections with family members already living in New York, and the rest of the family would follow in a year or two as the two younger boys approached conscription age. However, Jake also decided to travel the country a bit, including a stop in Lincoln, Nebraska. He liked it and thought that someday, he might be able to earn a living there as a tailor, which was the family trade. He returned to New York in time to meet his parents and two younger brothers – Harry, 16, and Isaac, 13 – as they arrived in 1891.

This part of the family story seemed relatively straightforward. They had a reason to leave and made a plan in line with that reason. Then, one day, I was looking at the family’s listing in the 1900 U.S. Census – probably for the umpteenth time. But this time, I noticed something I hadn’t before.

The 1900 census was the only census, so far as I know, that asked the wife of the head of household how many live births she had had, and how many of these children were alive in 1900. The numbers I saw in those columns stunned me. Suddenly, I realized that Barnet and Sophia had had eight children together, but only the three boys survived. They had lost five children. No way would they risk losing one – or more – of their growing boys through the evils of conscription. Thus, even though Barnet and Sophia were in their mid-50s, a difficult age to start over with no money and a new language, and 5,000 miles from home, they would do just that. What else could they do? There was: No. Other. Choice.

Barnet and Sophie chose to remain in New York, the port of entry, where 85 percent of the incoming Jews remained. Jake came to Lincoln and the middle brother, Harry, who would become my grandfather, joined him a few years later. Jake returned to New York, but Garson Bros., their tailoring business, would support Harry’s family in Lincoln for almost 40 years, until his death.

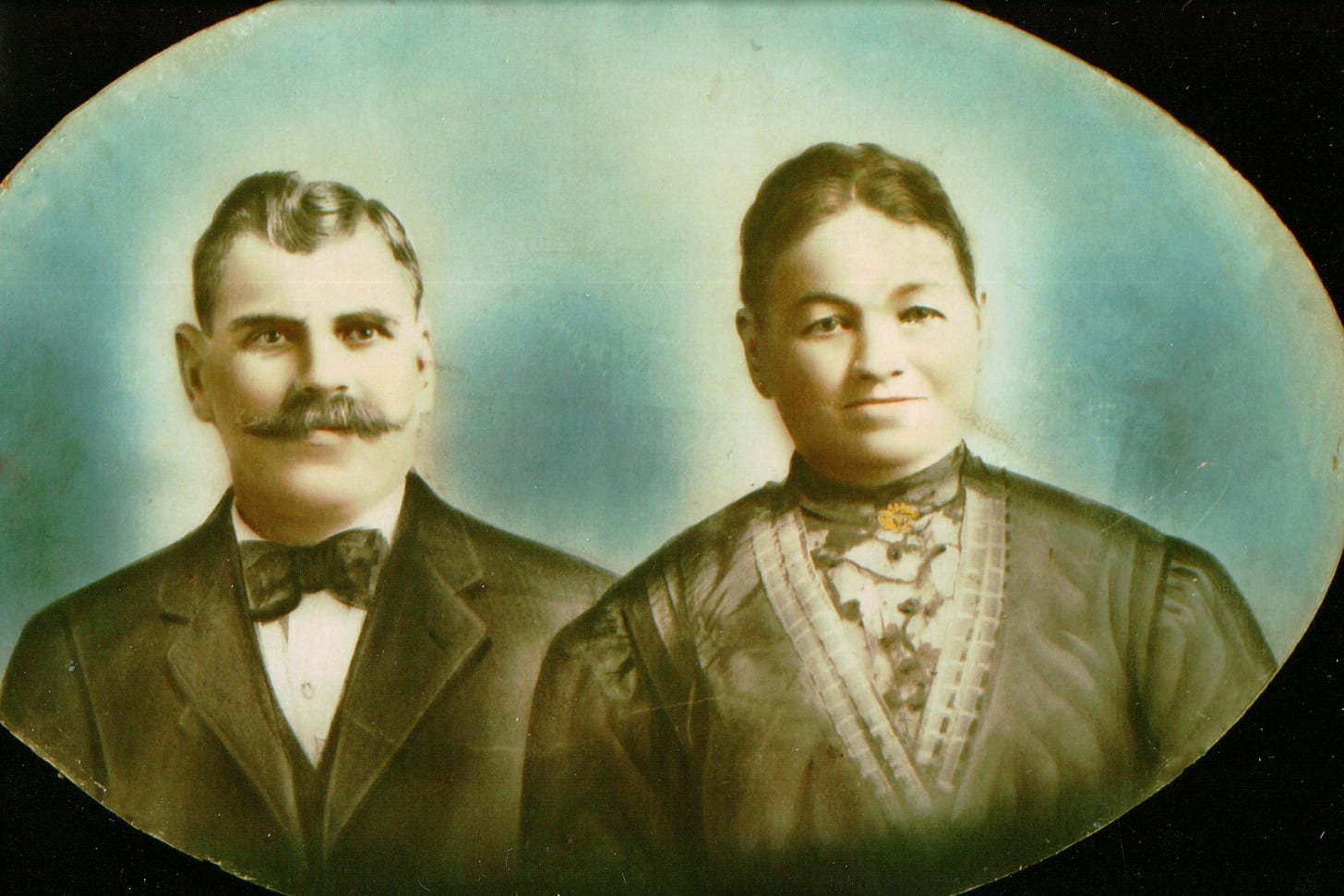

A broken leg that set a legal precedent

Solomon Greenstone left Poland for America in 1884. He settled in Lincoln for reasons that are not known. His wife, Lena (nee Ellis), and their three daughters followed a couple of years later, and three more children would be born in Nebraska. Although three of the six total children would die young in their new homeland, their firstborn, daughter Eva, would marry Harry Garson and they would become my paternal grandparents.

Solomon opened a pawn shop in Lincoln and the family prospered. But despite his financial success, Solomon had faced numerous obstacles in Lincoln, that came to light as I began researching his new life. Among other things, I learned that he was a fighter; he never met an obstacle he could not overcome. His places of business were destroyed by fire and victimized by brazen robberies. Local authorities seemed to be looking for ways to give him legal troubles, including arrests for operating his business without a license and failing to keep the required records. No slack was cut for a man still struggling with the language and laws of a new homeland. All of this paled, however, in comparison to the lifelong pain stemming from a broken leg that left him nearly a cripple.

His injury occurred as he was walking home from work on Sunday, October 24, 1897; yes, he worked on Sundays, although Saturdays were reserved for worship. A weak board in a wood sidewalk gave way as he stepped on it. His leg went through the hole in the walkway, breaking his tibia. The leg healed on its own — sort of. It never worked properly again. Solomon, a man with a strong will, wanted recompense from the city, arguing that it was responsible for his injury because it had not kept the sidewalk in good repair.

First, he went to the Lincoln City Council seeking damages. The Council treated him “as if he was not in existence,” a Lincoln newspaper reported in a somewhat direct hint at anti-Semitism. Now, Solomon was angry. He filed a lawsuit against the city. The city fought the claim and then tried to transfer the burden of paying damages to the owner of the property. The case dragged on for five years through three trials and two appeals. The city finally turned to an up-and-coming young lawyer, who was working for his father’s law firm. Roscoe Pound tried his best to find a path relieving the city of responsibility. In the end, the case went to the Nebraska Supreme Court, which ruled in a precedent-setting case that the city was responsible for sidewalk maintenance and had to pay. Solomon collected an $800 judgment from the city, the equivalent of $28,000 today. His lawyers did, however, state publicly, as the Lincoln newspaper reported, that the award would have been greater if their client had not been Jewish.

Roscoe Pound? His loss does not appear to have been much of a setback. He was named dean of the University of Nebraska Law School in 1911. Five years later, he was named dean of the Harvard Law School, a position he held for 20 years.

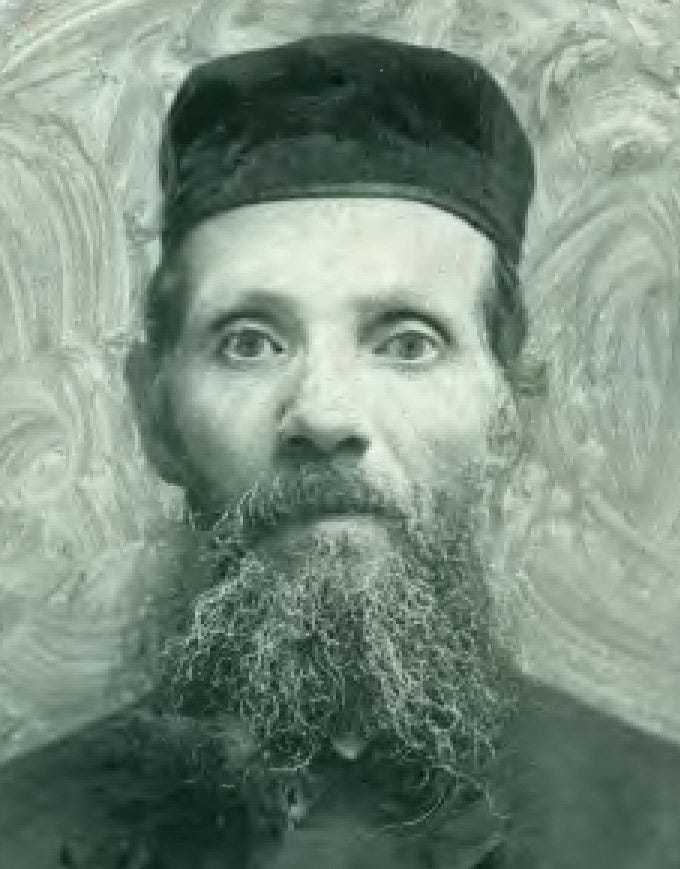

2 surprises: He married his step-sister, then he killed a man

Wolfe Krasne grew up in Bielsk, Poland, where his father operated an inn – essentially a tavern with overnight rooms for rent. Bielsk was a stopping point for travelers between two of Poland’s larger cities, Bialystok and Warsaw.

I did not know until I began digging that two other things set him apart from many men of his time: 1) That he and his wife, Tobe (nee Gottlieb), my great-grandmother, were step-siblings. 2 ) That he left for America in a great hurry because he killed a man, albeit in probable self-defense.

His job at the inn was what today might be called a bouncer. When someone drank too much and became rowdy, Wolfe stepped in to restore order. One night in 1893, a Russian soldier settled in for libation. He drank until he became trouble, which is when Wolfe, a large, muscular man, asked him to leave. There was an argument, then, a fight. The Russian soldier did not survive his backward fall through a second-story window. The story and its aftermath were pieced together from conversations with several older family members still surviving.

At his family’s urging, Wolfe left his wife and children in Bielsk that night and sneaked out of town. The Russian government, which controlled much of Poland, was not likely to listen to any explanation Wolfe might have given for attacking a Russian soldier who ended up dead. Wolfe made his escape to the border hiding beneath a load of hay in a horse-drawn wagon. He arrived in New York on May 27, 1893, settling in Aurora, Illinois. His wife, Tobe, and children, one of whom would become my maternal grandmother, followed a few years later. The reunited family settled in Omaha, where other Krasne family members resided. Wolfe opened a bathhouse (these were the years before indoor plumbing) and collected junk for resale on the side.

About marrying his step-sister: Again, it was a long, hard look at a census document, this time for the 1920 census, that provided the proof of a family story I had wondered about. In the column headed “Relationship of person to head of household,” the entry at first looked like an illegible scribble, and I had written it off as that. But upon magnified examination, the census taker had entered “Step-sister,” next to Tobe’s name – and then overwritten it in heavy hand and larger letters, “Wife.” Wolfe and Tobe had lived together in the same house since their early teen years after Wolfe’s father and Tobe’s mother, both widowed, had married. It must have seemed a natural progression of relationship to them. They married when she was 18 and he was 19. It may have been uncommon, but it was not illegal.

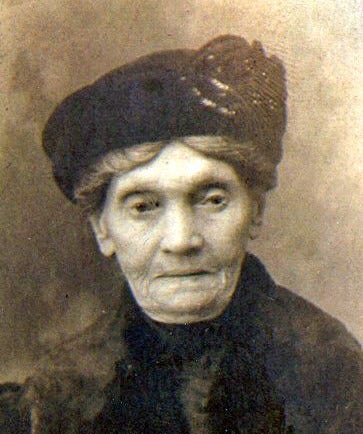

Too convenient to ignore: The brothel was almost next door

Louis Stine was about 22 when he left his hometown in Austria-Hungary in 1883 or ’84 and headed for America. Although the town was not in Russia, the Austrian military also may not have been a friendly place for Jews. But there may have been bit more to his decision to emigrate, I learned when I began interviewing older family members. He was likely running away from his wife.

Perhaps in line with this, he selected a relatively little-known city in mid-America, as well as a much less common spelling of his surname. His younger brother, Philip, chose the more common spelling, Stein, when he immigrated several years later. In any case, Louis, like Solomon Greenstone, opened a pawnshop in Lincoln, later transitioning to the more lucrative collection of hides, wool, and scrap metal.

In any case, if Louis intended to hide, he made one big mistake. His businesses did well, and, living alone in Lincoln, he had few expenses. He invested his earnings in real estate. He could not have chosen a better investment opportunity at the time. Within a few years, another resident of Louis’s hometown in Austria-Hungary happened to settle in Lincoln. He wrote home to tell of the remarkable success of Louis Stine. The letter made its way to Louis’s father-in-law, who promptly booked passage for his daughter to Lincoln.

Hinde (nee Mortkowitz) showed up unannounced one day in 1886 on Louis’s doorstep in Lincoln. My grandfather, Abe Stine, was born a year later.

Louis and Hinde Stine proceeded to have nine children. Though they had their problems together, they made their married life work.

However, Louis left one more secret hidden in Lincoln, and it remained hidden for more than 100 years. Then, a couple of years ago, I heard from a woman named Connie in Texas, who had recently received the results of her DNA test. She was stunned to learn that she was 12.5 percent Jewish. Through matching with my DNA, she determined that the connection was through the Stine family in Lincoln.

Though I had been working on Stine family research for many years, I had no idea who she was. Connie and I worked on the puzzle together.

The circumstances indicated that Connie’s grandmother was likely the product of a young unwed mother who had a relationship with one of the men in the Stine family. However, there were no Stine men in their 20s and 30s at the time her grandmother was born. We ended up with only one possibility among the Stine men: Louis Stine, despite a 30-year age difference with the young unwed mother, had to be the father. Never mind that Louis’s wife, Hinde, gave birth to her ninth child about six weeks after Connie’s grandmother was born.

There are various possibilities for how this might have happened. It seems possibly relevant, however, that two of Lincoln’s most widely known brothels operated illegally but openly within a five-minute walk of Louis Stine’s business location; also that Connie’s grandmother was born in Seward, Nebraska, the location of a state-financed home for unwed mothers, and the place prostitutes who got pregnant in Nebraska usually went to deliver their babies.

Welcome to the family, Connie.

Dig deep and you will find surprises

The overall message here is that if you dig deeply enough into your family, you are likely to find things you did not know. These discoveries may reveal critical decision points that virtually define who you are and how you came to be. They may uncover personality traits that explain things about your personality. Had it not been for Wolfe Krasne’s fight to the death with a Russian soldier, Barnet and Sophia Garson’s determination to save their sons from conscription, or Louis Stine’s financial success in America, I would not be here. And maybe I get my determination and commitment to pursue goals from Solomon Greenstone.

It is fascinating work that has captivated me for more than a quarter century. In addition to my own family, I work for clients through a small business I started, Family Stories by Arnold Garson. I research and write a book about my client’s family history. I begin with what the client already knows and build the research and story from there. I almost always find things the client did not know about his or her family; the secrets that have been buried.

My Iowa Writers’ Collaborative Colleague, Cheryl Tevis, wrote a wonderful Substack column recently on the importance of telling family stories to your children, thus preserving your family history. She was absolutely on target. I especially liked this paragraph from her column:

Recent research reveals that younger people who know intergenerational stories have more positive outcomes, including higher self-esteem, lower anxiety, and a higher sense of meaning and purpose in life. Marshall Duke and Robyn Fivush. https://www.seattlefoundation.org/the-do-you-know-scale/

What better motivation can you have for learning the history of your ancestors and sharing it? I would add that there never has been a better time to undertake family history research. Long-buried secrets are more likely to rise to the surface than ever before. There is more genealogy information readily available today, and the magic of DNA research, available at a modest cost, can provide unimaginable new horizons.

Building out your family history can be fun. It also is one of the greatest gifts you can give to your children and grandchildren.

Absolutely great column and will be an inspiration to all who’ve only mused about doing family history work to get going on it!

What wonderful, amazing detail you managed to draw out of your family stories! Thank you for writing and sharing this!