Why U.S. taxpayers are the biggest losers when tariffs are increased

The Two Kings of American Tariffs Learned the Hard Way

Tariffs are one of America’s oldest tools for raising money and trying to manage foreign affairs.

During the first 75 years of America’s history, they succeeded in doing both. Tariffs covered as much as 90 percent of the cost of running the American government in those years. It was a short-lived success story.

Over the past century or more, tariffs have constituted a complex, misunderstood, and largely failed attempt to repeat what they achieved in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Most recently, tariffs constituted a major effort by the Trump administration (2017-2021) to partly offset revenue losses from a tax cut benefiting the wealthy, and to penalize the Chinese. The Biden administration made some changes but mostly maintained the Trump tariff increases.

Full stop. This is not an anti-tariff column. There is a place and purpose for carefully selective tariffs in specific situations in America.

However, in today’s more complicated world, tariffs cannot reasonably cover enormous new spending or tax-cut commitments without effecting unacceptable results: increased inflation and job losses. They also result in damaging retaliatory actions by targeted foreign governments.

Farmers get hit hard by tariffs

Regarding the latter, retaliatory actions have hit Iowa particularly hard. China, a major target of the U.S. tariffs of recent years, responded with its own tariffs on carefully selected exports from the U.S. to China. U.S. products at the top of China’s list were agricultural products: soybeans, pork, and sorghum. Overall, agricultural products accounted for 22 percent of China’s new tariffs on goods it imported from the U.S.

One result was that U.S. ag products became more expensive in China – sufficiently more expensive to result in a drastic reduction of U.S. ag imports to China. From mid-2018 to the end of 2019, there was a 71 percent decline in U.S. soybean exports to China. Sorghum exports dropped by 7 percent, pork, by 5 percent.

Three states were disproportionately affected by these actions. Two of them were Illinois and Kansas. You knew three paragraphs ago what the third state is on the list.

Beneath the surface: How tariffs work

When the U.S. enacts a tariff, a foreign manufacturer that sells its products to an American company has to pay the tax when the goods arrive in the U.S. The problem is that the foreign manufacturer is going to raise the price of goods being sold to an American company, thus covering its cost of the tariff. The increased price then is passed along to consumers in the form of higher prices when the goods are sold in America.

If the imported goods are raw materials, say steel, the prices of all of the products in the U.S. made from that steel have to be raised to compensate for the U.S. manufacturer’s increased cost of steel. Consider, for example, a steel widget.

The price of the widget goes up to cover the cost of the new U.S. tariff the foreign manufacturer had to pay. Consumers may react to the increased price of a widget in different ways. Some will complain but buy the widget anyway at the increased cost. Others may walk away and look for a cheaper substitute, maybe a plastic widget. Or they may decide that they do not need a new widget after all.

Ultimately, there will be fewer steel widgets sold and the widget manufacturers must face decreased demand for their products. A decrease in the number of widgets sold inevitably results in decreased revenue, which, in turn, can easily translate to layoffs in the widget manufacturing industry.

In a real-case example, in 2018, when tariffs were greatly increased on steel and aluminum, it benefited the steel and aluminum industries by making foreign imports more expensive than steel and aluminum in America. However, employment decreased overall in America because the prices of the products made from those products increased. For every one job that was added in the steel and aluminum production industry in America, 16 jobs were lost in the industries that made products from steel and aluminum and had to increase prices to cover the tariffs.

In another example, manufacturers of more complex products often rely on the import of components made in foreign countries. When a tariff comes into play, the component is inevitably going to cost more. The U.S. manufacturer of the more complex product then has to raise prices to cover the cost of the tariff. Again, demand for the more expensive product will likely fall and the manufacturer may have to reduce employment to compensate. The result, again, is both inflation and job losses.

Meet America’s kings of tariff

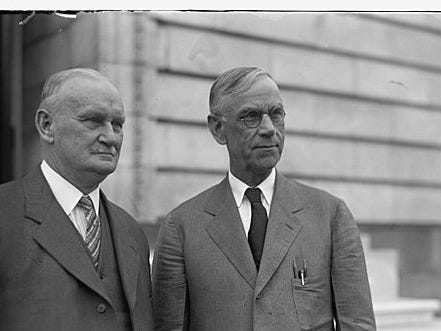

If they were alive, you could ask Reed Smoot and Willis C. Hawley about what enormous tariff increases could do to a political career.

Smoot and Hawley conspired in 1930 to craft near-record tariff increases in the belief that they would be advantageous to America. More than 1,000 economists argued that the increases would be detrimental to the U.S. economy. President Herbert Hoover appeared to believe them but yielded to pressure within his party and signed the bill into law.

Smoot and Hawley had promised prosperity as a result of the tariffs. The opposite impact was almost immediately apparent. Other factors assisted in bringing on the Great Depression as well, but Smoot, Hawley, and Hoover got the ball rolling.

Then came the 1932 elections.

Smoot had served 27 years in the Senate representing Utah. He lost his bid for a sixth term in 1932. Hawley, from Oregon, had been elected to the House in 1906. After 13 terms, he was defeated for re-election in 1932.

Yes, it was the Depression, but the bottom line is that the Smoot-Hawley tariff had exacerbated its impact. Much of the blame for what happened in the American economy fell on Smoot, Hawley, and Hoover.

Hoover got less than 40 percent of the vote in his run for a second term in 1932, one of the most overwhelming rejections in history. He would spend the rest of his life seeking his party’s nomination for a second term and being ignored.

All of which is something to think about in this election year.

NOTE TO MY READERS: I write this column, Arnold Garson: Second Thoughts, as a member of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative. You can subscribe for free. However, if you enjoy my work, please consider showing your support by becoming a paid subscriber at the level that feels right for you. The cost can be less $2 per column.

Sources for this column include but are not limited to: How Tariffs and the Tradfe3 War Hurt U.S. Agriculture, Alex Durante, Tax Foundation, July 25, 2022; Tariffs Are Costing Jobs: A Look at How Many, Stuart Anderson, Forbes, September 24, 2018; A Brief History of Tariffs in the United States and the Dangers of their Use Today, Tyler Halloran, news.fordhamlaw.edu; Trump Tariffs & Biden Tariffs: Economic Impact of the Trade war, Erica York, Tax Foundation, June 26, 2024; Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, wikipedia.com

Here is a link to the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative Sunday Roundup, where you can get a compilation of our members’ work published the previous week.

Iowa Writers Collaborative Roundup

Linking readers and professional writers who care about Iowa.

And after the soybean prices fell drastically, the MAGA forces raided the Treasury (or the Commodity Credit Corporation) to “rescue” the growers. Yet that voting bloc ignored all that by supporting DT again in 2020. So much for fiscal conservatism!

Thanks for this good perspective and commentary regarding a little-understood topic.